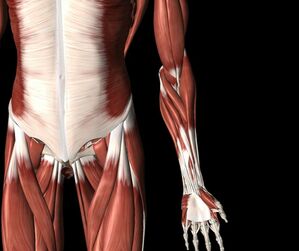

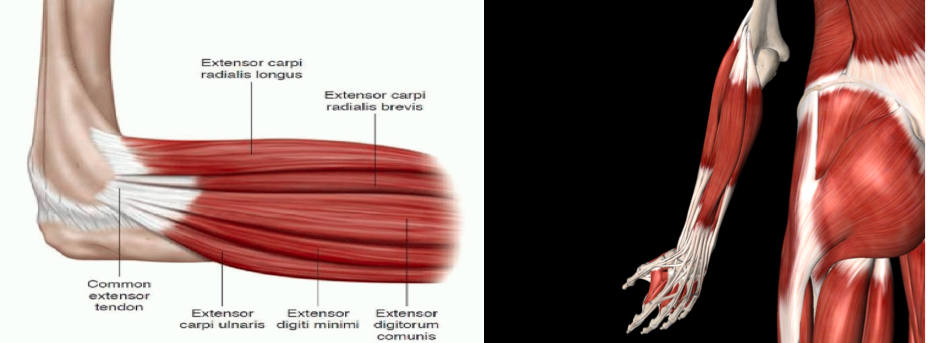

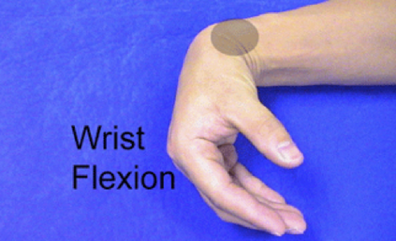

Tennis Elbow / Lateral Epicondylitis The outside of your forearm hurts and you do a quick Google search. You discover that the most likely cause of your pain is called Tennis Elbow. How could this be? You haven’t played tennis in years! Tennis elbow, or lateral epicondylitis, is the most common problem of the forearm/elbow. While it is treatable, not all tennis elbows are the same, and they have to be assessed and treated differently in order to ensure success. In this article I will outline some of the typical factors that lead to tennis elbow and how to ensure you have an appropriate treatment plan. Overuse Syndromes of the ElbowSixteen muscles cross the elbow joint. Nine of those muscles help to control our wrist and hand, and are used almost constantly throughout the day. These muscles also tend to get tight, be under-strengthened, and over-used. It’s a wonder why more of us don't develop forearm pain! The second most common reason for elbow pain is golfer's elbow (medial epicondylitis), which affects the inside of the elbow. here are many other tendon problems that can occur near the elbow: Some of the more common ones include an inflamed tendon of the biceps, brachialis, brachioradialis or the triceps muscles. Before going any further, check out this article on tendon dysfunction to learn more about how tendons work and why they become injured: www.jacobcarterphysiotherapy.com/articles/tendon-function-and-dysfunction Tennis ElbowTennis elbow can present as pain/discomfort/stiffness on the outside of the elbow at rest or when gripping objects, moving the wrist or fingers, rotating the forearm, or bending/straightening your elbow. Often there will be pain when palpating/touching near the lateral epicondyle. With chronic or very painful cases of tennis elbow, tears of the common extensor tendon may occur. This location is where most of the tendons that help to extend the wrist and fingers meet. Acute tennis elbow can often be solved in a matter of weeks, however pain that persists (often because of inadequate treatment of the condition) may take 6-24 months to fully resolve. The most important step required to initiate healing is to develop a plan that addresses all of the contributing factors. Factors that Contribute to Tennis Elbow Here are a few common factors that contribute Tennis Elbow, and possible treatment options: 1. Repetitive Movement and Excessive Load When tendons are required to withstand more volume or load than their structural integrity permits, the tendon will develop microscopic tears. The result is inflammation (which is actually important in the first stage of healing) and pain (due to the inflammation that activates local pain receptors). If you could simply allow the body to rest for 2-3 days, then start with some strengthening exercises, it is likely that your rehab would be much shorter. Most individuals that develop tennis elbow spend a large amount of time doing a single task such as repetitive administrative work (e.g. typing on a computer), repetitive manual labour (e.g. using a hammer or screwdriver), mountain biking, rock climbing, etc. The key step here is to ensure variety in physical tasks so that there is an equal growth of the supporting forearm musculature. We know that tendons respond best to slow increases in volume or load. An example of this would be a runner with ambitions of running a marathon: They will require at least a few months of slow progression in their training program to build strength of the connective tissue. 2. Forearm Muscular Imbalance Functionally, the forearm extensor group is most often engaged to keep the wrist in a neutral position as you use the forearm flexor group to grasp and manipulate various items with your hand/fingers. Without the forearm extensors, the wrist would simply flex forward as seen here: Therefore, if any of the other muscles that cause wrist or forearm movement (most significantly the wrist flexors) are tight, it often requires the wrist extensors to work excessively. If this increased load on the extensor tendon lasts long enough, tendinitis can occur. As mentioned earlier, the muscles that extend the wrist and fingers attach to the elbow via the common extensor tendon. There is always a fine balance of muscle strength to flexibility required for optimal function. If muscles are weak, excess strain is placed upon the tendon to absorb the forces applied during movement. If muscles are tight, there is a resulting increased strain placed on the tendons at baseline, as the muscles constantly pull on the tendon. 3. Shoulder Tightness As we expand our view to include the concept of regional interdependence, we must consider the shoulder, neck, and perhaps a focus on the thoracic spine, lumbar spine and pelvis. I would say that in my experience, it is possible to return an individual to their normal activities and sports by addressing the forearm alone in approximately 30% of cases. The other 70% of cases require an expanded view of the body. My reasoning for the success of addressing other areas of the body, in addition to the forearm, is as follows: 1. If we lack flexibility or strength at one joint, the neighbouring muscles and joints tend to make up for it. 2. If we have increased muscle tension in certain muscles, they may cause compression on the nerves that travel underneath of them and innervate the forearm muscles (e.g. the infraspinatus may compress the radial nerve at the shoulder, causing changes to the forearm muscles that are innervated by this nerve). 3. Compression of nerves at the neck, typically the lower cervical spine, can cause weakness to the muscles of the forearm and therefore be the cause of the forearm dysfunction… OR the nerve compression can refer pain to the elbow that mimics tennis elbow, causes pain when palpating the elbow and causes reduced strength to the muscles of the forearm. 4. Body Movement and Posture The body develops pain for a reason. Often that reason has, at least part, to do with how you move - There is probably a movement pattern to blame. To ensure full recovery, it’s important to use strategies and control-based exercises to address the poor movement patterns directly. This requires a skilled eye, knowledge of the sport, and ideally your Physiotherapist should watch how you move in your sport or at work. It is usually time consuming (and therefore, expensive) to have a Physiotherapist watch their clients perform their sport in person or go to their job site, but some video footage or photos can certainly help! A few strategies to improve work-related causes of tennis elbow may include adjusting (A) Computer seat height, (B) Keyboard position, (C) Size of grip on various tools required at work, (D) Amount of vibration you are required to control with tools at work, (E) Number of rest breaks. Treatment Options The initial stages of treatment for nearly any tendinopathy requires reducing muscle tension (via manual therapy and intramuscular stimulation (IMS)), addressing compensation patterns within the body, reducing the strain on the tendon by altering body mechanics, decreasing workload (rest), and possibly using braces/strapping. If the tennis elbow is acute (having started within the last 3-6 weeks), then focus should be placed on rest and ice for a few days to reduce the level of pain to a 3/10. If needed, you may consider taking analgesics (e.g. acetaminophen), however you may want to restrict the use of anti-inflammatory medications (e.g. ibuprofen) as recent evidence suggests that restricting the initial inflammatory process may impair healing. As the acute level of pain settles, it is now time to start with strength and flexibility exercises that are tailored to your unique presentation, and gradual re-introduction of the activity that initially caused pain. If the dysfunction is chronic (over 6 weeks worth of pain), the focus should be placed on increasing blood flow to the area, increasing the load tolerance of the affected tendons (via certain types of exercises) and Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy (ESWT). Shockwave therapy has proven very effective in cases of thickened tendons (due to collagen/scar tissue accumulation) and calcification build up. These treatment techniques are used at specific intervals of time, and allow the body to resume its natural healing process. In cases of tennis elbow that prove resistant to conservative treatment options, it may be helpful to consider other options: To rule out underlying pathology your Physiotherapist or Physician may refer you for diagnostic imaging, which may include an x-ray, ultrasound or MRI. Based off of these findings, a Sports Medicine Physician may consider an injection to reduce inflammation or encourage healing. The most popular injection options include corticosteroid (cortisone), prolotherapy, or platelet-rich protein (PRP). Conclusion No two cases of tennis elbow are exactly alike. It is important to understand the contributing factors that led to the dysfunction, and understand which stage of healing the injury is in. In more complicated cases that fail initial Physiotherapy management, diagnostic imaging may be warranted. Once all of this information is gathered, a skilled Physiotherapist or Sports Medicine Physician can then create a comprehensive plan that will maximize your success.

1 Comment

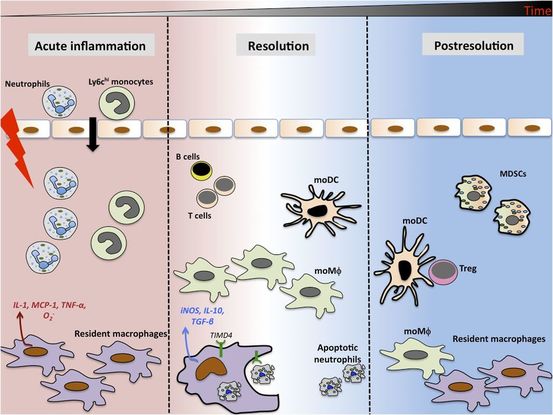

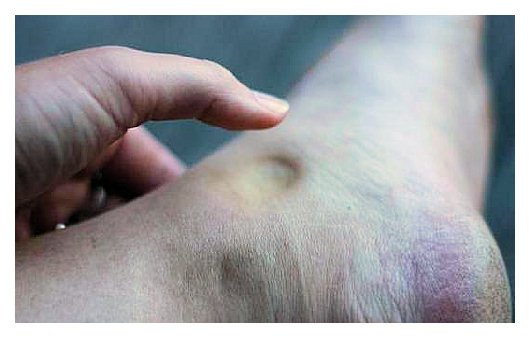

As written for www.one-wellness.ca We try to improve the body’s natural response to injury in many different ways. Health professionals around the world offer products and techniques that promise the greatest reduction in inflammation and swelling, believing that their product can rise above the competition… But why? Is it helpful to alter these responses, and is it even possible that we can alter these responses? For the most pragmatic answers, we can rely only on research… Definitions Understanding the differences in medical terminology allows us to better understand what processes are happening in our body. With this higher level of understanding, both practitioners and patients can better communicate what is happening in the body to achieve optimal outcomes. Swelling and inflammation of are often thought of as synonymous terms, however they have distinct definitions and applications. Inflammation: Inflammation is “a local response to cellular injury that is marked by capillary dilatation, leukocytic infiltration, redness, heat, and pain and that serves as a mechanism initiating the elimination of noxious agents and of damaged tissue” (1). Swelling: From Greek, the word ‘oídēma’ translates to ‘swelling’ (2). ‘Edema’ suggests “an abnormal infiltration and excess accumulation of serous fluid in connective tissue or in a serous cavity” (3). To briefly summarize, inflammation is a cellular response to tissue injury and may result in swelling, however swelling can actually occur within the body without the process of inflammation. A few common examples of swelling occurring within the body, in the absence of inflammation include: Lymphedema (failure of lymphatic drainage system to circulate blood plasma, and immune system regulators), cerebral edema (accumulation of extracellular fluid in the brain), pulmonary edema (accumulation of extracellular fluid in the lung). A few common examples of swelling that occurs within the body with inflammation as the causation includes: Acute tissue injury (fractures, sprains, strains), dermatitis (inflammation of the dermis layer of the skin), thrombophlebitis (inflammation of vein due to a blood clot). Treating Inflammation Is it possible to alter the inflammatory response? Is it helpful to alter the inflammatory response? Over the last few decades there has been a culture of reducing inflammation immediately following acute injuries. However recent research has been changing the way clinicians should treat acute injuries: Anti-inflammatory medication can decrease the inflammatory response, but they may impair healing: In addition to their potential side effects (affecting GI tract, kidneys and cardiovascular systems), using NSAIDs (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) may result in: a) Impaired bone healing after a fracture (4-9). b) Impaired tendon healing after an acute injury (10-11). c) No improvements in chronic tendinopathies, as there is no active inflammatory process (12). d) No improvement or possible small improvements in functional recovery In acute ligament injuries (13-18). Although one study found that using NSAIDs resulted in decreased pain and improved functional status, they also found a greater risk of adverse affects compared to using only analgesics. Also, one review of the literature found that acetaminophen is as effective as NSAIDs for pain reduction after musculoskeletal injury (19). These new results teach a few lessons: 1) The inflammatory mediators (e.g. prostaglandins, and cytokines) in inflammation help to initiate the subsequent stages of healing. 2) Removal of inflammation from an acute injury may harm the subsequent stages of healing. 3) In many cases, acetaminophen (e.g. Tylenol) will help to reduce pain as much as the use of anti-inflammatory medications, and will not impair healing. The overall justification for the use of the RICE principle (Rest, Ice, Compression Elevation) is very practical and helps minimize bleeding into the injury site. However, there has not been a single randomized, clinical trial to validate the effectiveness of the entire principle. 50 There is some support for each item, including immediate rest, and elevation to help in managing the accumulation of interstitial fluid (20). Summary: As much as possible restrict the usage of NSAIDs, employ the RICE principle, and if pain requires additional control then consider the use of other analgesic medications (e.g. acetaminophen, opiods, etc). It is a counterproductive goal to attempt to resolve all inflammation around the acute injury site. Treating Swelling Is it possible to alter swelling caused by acute injuries? Is it helpful to alter the swelling? It is possible to alter swelling that has been caused by acute injuries. In the following photos you can see that with appropriate rehabilitation, swelling improves. Unlike inflammation, it is in your best interest to reduce the amount of swelling at the local injury site. Depending on the amount of swelling, it can result in nerve compression, and restricted joint mobility making it painful and difficult to move the affected area (21). There is no benefit of allowing this swelling to stagnate as it will increase the level of irritability of the injury site and cause further deconditioning. While there are numerous modalities that purport to increase blood flow (e.g. interferential current, acupuncture, laser, ultrasound, etc., they majority lack substantial research and are unnecessary to resolve 99% of cases. In addition to the RICE principle mentioned previously, there are two supported methods to reduce swelling at the injury site: Movement - Regular movement of the affected joint, or at least the joints above and below should help pump the excess fluid back toward your heart using the lymphatic system. In addition, when able, start to perform cycling, swimming, rowing or perform upper body exercises. Massage - Stroking the affected area toward your heart using firm pressure may help move the excess fluid out of that area. There are many physiotherapists and massage therapists that have extra training in lymphatic drainage techniques that may be able to guide you, if you have been experiencing poor outcomes. References 1. Merriam-Webster Dictionary [Internet]. 2018. Inflammation; 2018-07-28. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inflammation

2. Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus 3. Merriam-Webster Dictionary [Internet]. 2018. Edema; 2018-07-28. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/edema 4. Matsumoto MA, De Oliveira A, Ribeiro Junior PD, et al. Short-term administration of non-selective and selective COX-2 NSAIDs do not interfere with bone repair in rats. J Mol Histol. 2008;39:381-387. 5. Endo K, Sairyo K, Komatsubara S, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor delays fracture healing in rats. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:470-474. 6. O’Connor JP, Capo JT, Tan V, et al. A comparison of the effects of ibuprofen and rofecoxib on rabbit fibula osteotomy healing. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:597-605. 7. Bergenstock M, Min W, Simon AM, et al. A comparison between the effects of acetaminophen and celecoxib on bone fracture healing in rats. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:717-723. 8. Giannoudis PV, MacDonald DA, Matthews SJ, et al. Nonunion of femoral diaphysis: the influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B:655-658. 9. Bhattacharyya T, Levin R, Vrahas MS, Solomon DH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and nonunion of humeral shaft fracture. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:364-367. 10. Elder CL, Dahners LE, Weinhold PS. A cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor impairs ligament healing in the rat. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:801-805. 11. Ferry ST, Dahners LE, Afshari HM, Weinhold PS. The effects of common anti-inflammatory drugs on the healing rat patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1326-1333. 12. Aström M, Westlin N. No effect of piroxicam on achilles tendinopathy: a randomized study of 70 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:631-634. 13. Lane LB, Boretz RS, Stuchin SA. Treatment of de Quervain’s disease: role of conservative management. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26:258-260. 14. Dahners LE, Gilbert JA, Lester GE, et al. The effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug on the healing of ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:641-646. 15. Moorman CT 3rd, Kukreti U, Fenton DC, Belkoff SM. The early effect of ibuprofen on the mechanical properties of healing medial collateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:738-741. 16. Ekman EF, Fiechtner JJ, Levy S, Fort JG. Efficacy of celecoxib versus ibuprofen in the treatment of acute pain: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial in acute ankle sprain. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2002;31:445-451. 17. Ekman EF, Ruoff G, Kuehl K, et al. The COX-2 specific inhibitor Valdecoxib versus tramadol in acute ankle sprain: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:945-955. 18. Slatyer MA, Hensley MJ, Lopert R. A randomized controlled trial of piroxicam in the management of acute ankle sprain in Australian Regular Army recruits. The kapooka ankle sprain study. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:544-553. 19. Feucht CL, Patel DR. Analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications in sports: use and abuse. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:751-774. 20. van den Bekerom MP, Struijs PA, Blankevoort L, Welling L, Van Dijk CN, Kerkhoffs GM. What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults?. J Athlet Train. 2012 Jul;47(4):435-43. 21. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s Principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. 18th ed; 2011. Change is sweet... but often takes time. I have been working with a 40 year old female climber for four weeks now (yes, I realize the photos are of me, and not of a female!). She came in to me with neck pain, and extremely limited neck range of motion. Although our treatments focused on a number of limitations including hip mobility, thoracic spine mobility and control, neck mobility and control and scapular mobility and control, we decided that two tests would be our most relevant measurable outcome measures: 1) Chin to Clavicles and 2) Chin to Chest. Give it a try: You should be able to easily touch your chin to your chest and to your clavicles. These two tests, when measured from a tall standing posture, take into account the mobility all of our posterior cervical muscles, our thoracic paraspinals, and our ability to attain full flexion of the cervical and upper thoracic vertebrae. My client was negative 4 cm from the chest and 5cm from each of the clavicles.

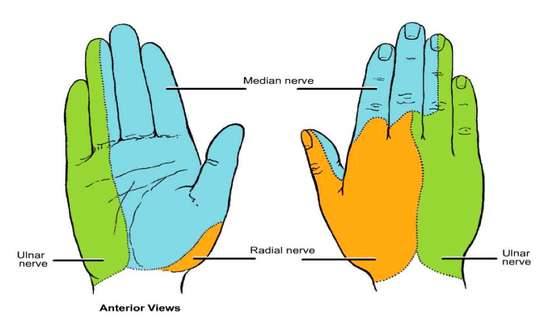

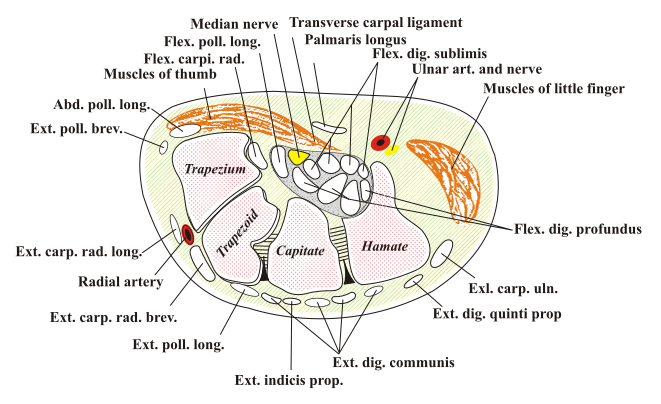

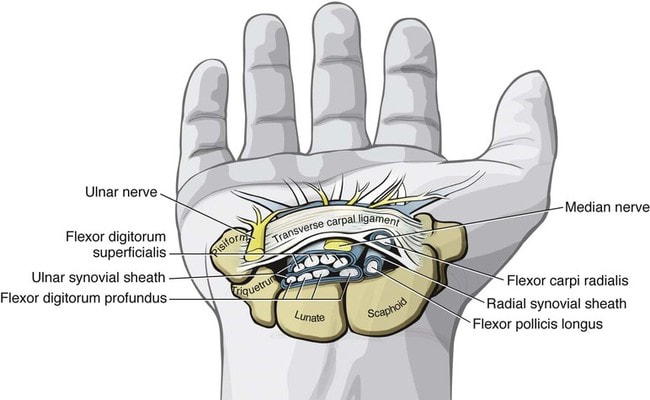

Touch down: My client was highly motivated to create change, and today it paid off! Over four weeks, 10 treatments and daily home exercises, she finally succeeded on passing both tests. She can’t remember when last she had this amount of neck mobility... but it was certainly not for the last 20 years. Also, and more importantly, she no longer experiences neck pain. For generalization sake, this took 1 month of hard work, at least a couple dozen hours of hard work at home and in clinic, and required changing daily postural and movement habits. While 1 month may seem like a long time, adaptation takes time without causing injury. I honestly would have been pleased with 2 months. What areas of your body are you trying to change?! Even Physiotherapists get Injured... I've been afflicted by, and recovered from dozens of injuries over my lifetime. Through this process I've acquired humility, experienced an endless variety of pain and learned a whole lot about what constitutes effective rehab! I wrote this article in the hope of sharing how I executed my own rehabilitation from carpal tunnel, and to share a few ideas for anyone currently dealing with carpal tunnel. Day 0 - Doomsday! Client History I had absolutely no idea that I would walk away from a casual day of rock climbing with carpal tunnel symptoms. While I had rock climbed less than 15 days in the previous 6 months, I had gone ice and mixed climbing over 60 days in that same time period. My typical week would consist of the 3-4 days of climbing, 1 day of weights in the gym, 1 day of core, and 2 days of mobility work. So what's my point? I was active and was not dealing with any injuries. Mechanism of Injury While leading a relatively easy route in Cougar Canyon, I found myself at the bottom of the crux: An overhang with a larger sloper, that would transition to a mantle. The problem of the route, was that you really had to get high on the sloper in order to find the higher hand placement, so that you could switch the a mantle position, and as a result my hand and wrist position looked like this: In all reality, I didn't make it to the position shown in the second photo, but this would have been the goal. Instead I exerted effort through the position shown in the first picture multiple times, ignoring the warning signs of slight numbness and tingling into my hand for about 5 minutes of effort and attempts. Leaving the crag, my finger sensation felt impaired and the palm of my hand felt a bit sensitive. I thought that it only needed a couple days of rest - I was wrong! Diagnosis: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (secondary to (1) flexor digitorum profundus and superficialis tendinitis and (2) sprain of the transverse carpal ligament). Prognosis (how long until injury is healed): On the day of injury, I had no idea! There was no pain, but the numbness was concerning. From my experience, any injury involving nerves is likely to take several weeks to several months. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome requires careful treatment and avoidance of aggravating positions, or it can turn into a chronic injury that may even require surgical intervention. Day 1 - 3 Numbness and tingling of my hand matched the pattern of median nerve distribution and the symptoms continued to get worse during these first few days. As the mechanism of my injury was one of overuse with compression, I would theorize that my carpal tunnel symptoms were likely caused by a tendonitis involving at least a few of the four flexor digitorum profudus and four flexor digitorum superficialis tendons. The space in which the tendons are contained in the carpal tunnel is not forgiving. There is very little space for inflammation, or thickened tendons (that may result from the local inflammation). This is why, in chronic or severe cases, a surgeon may cut the transverse carpal ligament in an effort to decrease any compression underneath of it. For these first few days I followed this treatment regime: 1) Avoided using my hand as much as possible at work and in my life. Purchased a wrist splint to sleep with and use when possible to keep wrist in a neutral position. 2) Ice packs applied to palm of hand and carpal tunnel = 3-5 times a day for 10 minutes 3) Massage of forearms with moderate pressure = 2 times a day for 5 minutes 4) Stretching wrist into extension with variations of elbow straight and elbow bent = 10 times a day for 15-30 seconds 5) Ibuprofen = 3 times a day using 400mg Note: All exercises and stretching were done to sub-symptom thresholds - AKA I did not aggravate my symptoms! Day 4 - 14 It was only after four days that it finally sunk in: Progress would be slow. This is quite common with carpal tunnel due to the combination of nerve irritability when inflammation is present, the length of time required to rehabilitate tendons, and the required use of the hand/fingers in most daily activities. Updated Prognosis: 3-9 months I advanced my rehab program to include the following: 1) Return to normal exercise programming as able: Lifting weights with lower body in the gym, hiking/biking 45-90 minutes each day. 2) Ice pack and hot packs applied to palm of hand and carpal tunnel = 3 times a day for 10 minutes each. 3) Massage of forearms with moderate to hard pressure = 2 times a day for 5 minutes. Also purchased an "Arm Aid" to help aid in future release of forearms over the upcoming weeks. 4) Released pec minor and back of shoulder with a lacrosse ball, due to having postural tightness on the left shoulder girdle - 1 time a day for 3 minutes each. 5) Stretching wrist flexors by going into wrist extension with variations of elbow straight and elbow bent = 10 times a day for 15-30 seconds 6) Isometric wrist flexion: 5 days a week - 3 sets of 8 reps. 5 seconds on, 10 second off. I standardized this by holding a dumbbell, and gradually increasing the weight. This exercise was important to start with very light weights, yet in the first week after injury, to encourage the tendons that pass through the wrist to start adapting to small amounts of load again. See photos below. 7) Resisted wrist extension and radial deviation. 5 days a week - 3 sets of 8 reps each. These exercises would develop muscular effort within the forearm, without irritating the structures within the carpal tunnel. See photos below. 8) Median nerve glides - 5 times a day for 15 reps. 9) Diclofenac gel = Applied 3 time a day to carpal tunnel and palm of hand Week 2 - 6 After completing 2 weeks of rehab exercises, my focus switched to strength training in the gym for one month. Each strength session was separated by at least 48 hours of rest, and I continued a selection of the above bullet points (# 1, 3 and 5). I returned to a progressive strengthening program inclusive of most exercises, but set three rules: (1) Ensure a neutral wrist (no wrist movement permitted in any loaded exercises), (2) No excessive pressure allowed to be placed on the carpal tunnel, and (3) No excessive amount of strain placed on the finger or wrist flexors. A few examples of exercises that I omitted were: (1) weighted pull ups (2) Heavy Rows, and (3) push ups. Additionally, each exercise session included isotonic (normal) wrist flexion, wrist extension, supination/pronation, and radial deviation exercises using a dumbbell. I would perform 3 sets of 8, taking 5 seconds for the concentric and eccentric phase, and allow 3 minutes of rest in-between each set. My goal was to develop load tolerance of the tendons, without causing any inflammation/irritation. Week 6+ I was comfortable performing nearly all exercises in the gym now, so at week 6, I returned to rock climbing. At first I started slowly in the climbing gym, and only committed to moves that allowed me to maintain a neutral wrist. I kept both the intensity and duration low for the first month. After 4 weeks of climbing inside, I returned to climbing outside with no worsening of my symptoms. Conclusion It has been 4 months since the initial injury, and my sensation still remains slightly impaired: I would give it a grade of 95%. Some things take time... and nerves are said to heal at a rate of 1 mm/day. From my carpal tunnel to the tip of my middle finger is 22cm long. That means it may take 220 days (or over 7 months) to see full resolution.

We may wish that healing could take place overnight, but nearly all rehab plans contain a common theme: Time, strengthening, mobility work, and a careful return to sport. Although I've taken several courses that address concussion assessment and treatment over the last few years, research is continually advancing our knowledge of guidelines. Here is a summary I've put together of some of the most recent literature which aims to answer the questions: Which patients require concussion rehabilitation and what does recent evidence suggest that concussion rehabilitation should include? Assessment and Treatment Timelines The most recent International Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport (The Berlin Consensus Statement, April 2017) states that evidence-based treatment for persistent concussion symptoms includes cervical spine treatment, vestibular rehabilitation, psychological interventions, and controlled submaximal exercise (1). The diagnosis of a concussion is a clinical judgment, made by a medical professional (1). A multi-faceted treatment approach seems to be the most effective approach to rehabilitation, and should begin immediately by obtaining a comprehensive history, performing a neurological exam to rule out serious pathology related to traumatic brain injury (TBI) or vascular insufficiency, and screening the cervical spine for signs of trauma. As a minimum, the health care team involved in the patient’s care should include a Family Physician and/or Sports Medicine Physician, and a Physiotherapist trained in concussion management. As required, patients may also benefit from a referral to see a psychologist, optometrist or dietician trained in concussion management. Recent evidence suggests that starting rehabilitation as early as 10 days after injury improves recovery time and decrease the risk of developing post-concussion syndrome (PCS) (2). For individuals with PCS, a multifaceted assessment is needed to identify targeted treatments that may be of benefit (3). Cervical, Vestibular, and Oculomotor Rehabilitation The amount of force necessary to sustain a concussion is far greater than that which is needed to sustain a whiplash (4). As a result, nearly every concussion sustains a whiplash as well. The significance of this fact is that whiplash injuries can disrupt the vestibular system (causing dizziness and vision dysfunction), result in cervical joint and muscle tightness/inflammation (causing local pain, referred headaches, and contribute to a lack of concentration), and disrupt the reflexes between cervical-vestibulo-occular system. In 2014, Schneider et al., published one of the first randomized clinical trials comparing a group receiving a combination of cervical and vestibular rehabilitation versus a control group that was given the usual protocol of rest followed by gradual exertion. Both groups received treatment from a physiotherapist at least once per week for 8 weeks, and had an average age of 15 years. In the treatment group, 73% of the participants were medically cleared within 8 weeks of initiation of treatment, compared with 7% in the control group. Individuals in the treatment group were 3.91 (95% CI 1.34 to 11.34) times more likely to be medically cleared by 8 weeks (2,5). In 2017, Reneker et al., published another randomized clinical trial comparing individualized treatment plans consisting of manual therapy of the neck, vestibular rehabilitation, oculomotor and neuromotor retraining, to a control group. Subjects were permitted by a sports medicine physician to enroll in the trial if they had experienced concussive symptoms for at least 10 days, and were treated by a Physiotherapist for up to a maximum of 8 visits or until they were fully cleared to return to play by a blinded sport-medicine physician. The progressive treatment group achieved symptom resolution and clearance to resume full sport activities significantly sooner than the control group: 15.5 days versus 26 days, respectively. The authors concluded that a personalized treatment plan beginning as early as 10 days after concussion may be an effective option to shorten recovery time (6). Exercise Recommendations Post-Concussion Initiating physical activity within the first 7-14 days post-concussion has been associated with a decreased risk of developing PCS. These results have been noted in adolescents and adults (7-12). Several clinical trial have demonstrated significant improvements in symptoms, cerebral blood flow mechanics, and complete return to all pre-injury activities over a much faster timeline compared to control groups or sham therapies (i.e. stretching). This is true for both acute concussions and PCS (7-10). Research would suggest performing low-level aerobic exercise most days of the week, at 80% of their symptom-tolerated heart rate (13,14). Summary: Providing Effective Treatment In addition to a graduated ‘Return to Learn’, ‘Return to Work’, and/or ‘Return to Play’ protocol, patients recovering from concussions seem to benefit the most from specific therapies for the cervical spine, vestibular system, visual system, and cardiovascular system. Research suggests that focused rehabilitation that begins within the first 7 to 10 days after injury can significantly improve outcomes and decrease long-term symptoms in both children and adults. References 1) McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, Aubry M, Bailes J, Broglio S, Cantu RC, Cassidy D, Echemendia RJ, Castellani RJ, Davis GA. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Apr 26:bjsports-2017.

2) Schneider K, Meeuwisse W, Nettel-Aguirre A, Boyd L, Barlow KM, Emery CA. Cervico-vestibular physiotherapy in the treatment of individuals with persistent symptoms following sport-related concussion: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2014 May 1;48:1294-8. 3) Feddermann-Demont N, Echemendia RJ, Schneider KJ, Solomon GS, Hayden KA, Turner M, Dvořák J, Straumann D, Tarnutzer AA. What domains of clinical function should be assessed after sport-related concussion? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jun 1;51(11):903-18. 4) Marshall CM, Vernon H, Leddy JJ, Baldwin BA. The role of the cervical spine in post-concussion syndrome. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2015 Jul 3;43(3):274-84. 5) Schneider KJ, Meeuwisse WH, Barlow KM, Emery CA. Cervicovestibular rehabilitation following sport-related concussion. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Jan 1;52(2):100-1. 6) Reneker JC, Hassen A, Phillips RS, Moughiman MC, Donaldson M, Moughiman J. Feasibility of early physical therapy for dizziness after a sports‐related concussion: A randomized clinical trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017 Dec 1;27(12):2009-18. 7) Baker JG, Freitas MS, Leddy JJ, Kozlowski KF, Willer BS. Return to full functioning after graded exercise assessment and progressive exercise treatment of postconcussion syndrome. Rehab Res Pract. 2012. 8) Leddy JJ, Cox JL, Baker JG, Wack DS, Pendergast DR, Zivadinov R, Willer B. Exercise treatment for postconcussion syndrome: a pilot study of changes in functional magnetic resonance imaging activation, physiology, and symptoms. J Head Trauma Rehab. 2013 Jul 1;28(4):241-9. 9) Gagnon I, Grilli L, Friedman D, Iverson GL. A pilot study of active rehabilitation for adolescents who are slow to recover from sport- related concussion. Sci and J Med Sci Sports. 2015; 26(3):299–306. 10) Imhoff S, Fait P, Carrier-Toutant F, Boulard G. Efficiency of an active rehabilitation intervention in a slow-to-recover paediatric population following mild traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. J Sports Med. 2016. 11) Lal A, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Ghajar J, Balamane M. The Effect of Physical Exercise after a Concussion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017 Jun 1. 12) Zemek R, Grool AM, Aglipay M, Momoli F, Meehan WP, Freedman SB, Yeates KO, Gravel J, Gagnon I, Boutis K, Meeuwisse W. Relationship of early participation in physical activities to persistent post-concussive symptoms following acute paediatricpediatric concussion. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jun 1;51(11):A20. 13] Schneider KJ, Leddy J, Guskiewicz K, Seifert TD, McCrea M, Silverberg N, Feddermann-Demont N, Iverson G, Hayden KA, Makdissi M: Rest and specific treatments following sport-related concussion: A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Mar 24, 51:930-4. 14) Leddy JJ, Kozlowski K, Donnelly JP, Pendergast DR, Epstein LH, Willer B. A preliminary study of subsymptom threshold exercise training for refractory post-concussion syndrome. Clin J Sport Med. 2010 Jan 1;20(1):21-7 |

Have you found these article to be informative, helpful, or enjoyable to read? If so, please visit my Facebook page by clicking HERE, or click the Like button below to be alerted of all new articles!

Author

Jacob Carter lives and works in Canmore, Alberta. He combines research evidence with clinical expertise to educate other healthcare professionals, athletes, and the general public on a variety of health topics. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed