Consistent Training Leads to Skilled Running Most athletes will attest that consistency is the most important aspect in progressing fitness and skill through training. This is why injuries set you back from reaching your full potential, or at least reaching goals in a timely fashion. While running, there are many things we can do to prevent injuries and some of them require very little time to implement, although learning the most effective way to implement them is individualized and may take years to achieve personal efficiency. Indeed, running is a skill, and it takes a long time to learn how to use your body in the most effective way. With a good training plan you will improve your efficiency, which will reduce physical and mental fatigue, reduce injury risk, and ultimately improve your performance! If you are new to running, or are simply wanting to improve, try these movement tweaks the next time you head out the door. N.B . These tweaks are good guidelines, but if you have a preexisting dysfunction (remember a dysfunction may not present with pain or any other symptom), you may benefit from a personalized approach. If you fall into this group, book in for a running assessment or seek guidance from a running coach, or rehab professional with post-graduate training in running assessments. It's Much More Than One Foot in Front of The Other 1) Upright posture. "Be tall!" At the start of your run, and periodically during your run, remind yourself to be tall. Think about elongating your entire spinal column; That is... if you had a string attached to the top of your head that connects down through the middle of your body, think about pulling that string up! You should not dramatically change your spinal curve with this, but you should feel that you are slightly taller. Why? When done appropriately, this helps to engage your multifidus muscles (spinal stabilizers), and make you aware of your core. This will help prevent energy loss due to poor stability, and will better allow you to apply force through your hips - helping to propel you forwards. It also helps with diaphragmatic activation and reduces the amount of airway resistance during breathing. PS - it might be a good idea to start thinking about upright posture during the rest of your day, as we spend thousands of hours hunched over at work and at home each year, and BELIEVE IT OR NOT!, this affects our athletic performance! 2) Forward lean from the feet / ankles "Lean forward from the ankles!" Running should be efficient. Leaning forward from the ankles aids in this efficiency, because it moves your center of mass slightly forward, and allows you to fall into your next stride. Don't forget #1 - it is too easy to let your forward lean come from hinging at the hips - "Stay Tall", and keep your head up, as you need to be looking forward! 3) Posterior-chain propulsion "Push, don't pull!" If we lean forward from the ankles, we will fall forward and must flex our hip joint and extend our knee to "catch" us from falling on our face. We can use this forward energy most effectively by pushing ourselves forward, as soon as our foot hits the ground. Try to see if you can feel yourself pushing forward using your glutes, hamstrings and calves. 4) Shortened stride and increased cadence "Shorten your stride and increase your cadence!" "Imagine that you are a ball, and as you are rolling over the ground, you are attempting to touch as many different places on the ground as possible" Most research suggests that elite runners who stay injury-free run with a cadence between 160-190 BPM. In most runners this improves multiple metrics (decreased "breaking phase", decreased vertical oscillation, decreased need for force absorption), and ultimately it decreases the amount of wear and tear / abuse placed on joints and muscles. In addition, it is said to improve efficiency in the long-term after the athlete adjusts to running in this way. The best place for our foot to land is directly under our center of mass because it minimizes the "breaking phase". The breaking phase is best described as wasted energy in the time between the foot striking the ground, and the push off phase when we propel ourself forwards. To ensure that we land with a vertical tibia - it is crucial to having a high cadence and a shortened stride. 5) Land with your foot under your center of mass "Most often, you should land using a midfoot strike" The jury is still out on what the best type of foot strike looks like in endurance athletes, but here is what we do know: A) A midfoot strike is mostly likely to place the foot under your center of mass while running on flat ground. B) Landing with a forefoot strike lends to a 2.6 times decrease in injury risk compared to rearfoot strikers (1). C) Landing on the forefoot or midfoot places more stress on the foot musculature and Achilles tendon. Landing on the rearfoot places more compressive loading forces at the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints of the knee. C) Rearfoot strikers tend to land with their foot in front of the body, which leads to have a longer stride and greater vertical loading (increased forces applied to the body) (2). D) Wearing shoes with larger heels lends to heel striking, whereas taking shoes off leads to landing on the forefoot or midfoot, with the strike being closer to the body. As always, we are reminded that science has limitations and common sense prevails, therefore do what feels right... BUT my recommendation would be to run on variable terrain, AND: A) As you run uphill, strike with your forefoot or midfoot. B) As you run the flats, strike mostly with your midfoot. C) As you run downhill, midfoot or heel strike may be best. Concluding Remarks These are but a few ways to immediately change your running form, in an effort to improve efficiency and promote injury-free training. General recommendations are terrible because they assume that all people are alike, so make no mistake - it is probably best to have a running assessment done to determine whether you truly need to change your running form. Nevertheless, exposing yourself to learn different styles of running will grow your running skill-sets and your body's durability, ultimately making you a better athlete! References 1) Daoud, Adam I., et al. "Foot strike and injury rates in endurance runners: a retrospective study." Med Sci Sports Exerc 44.7 (2012): 1325-34.

2) Williams III, Dorsey S., Irene S. McClay, and Kurt T. Manal. "Lower extremity mechanics in runners with a converted forefoot strike pattern." Journal of Applied Biomechanics 16.2 (2000): 210-218.

0 Comments

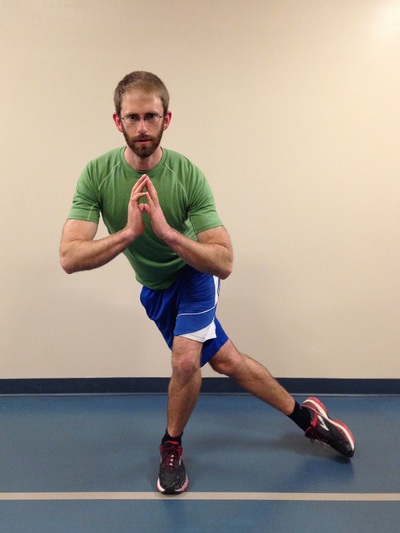

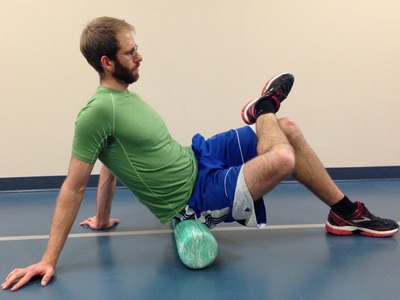

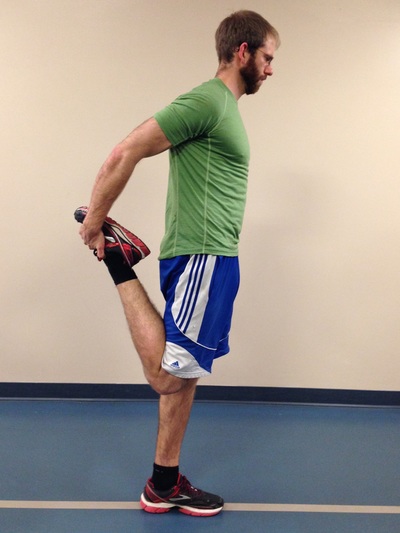

The Great Outdoors. It is there for you to enjoy, to push your limits, and develop fortitude. For some people, going outdoors can be synonymous with developing injuries, but there are steps you can take to mitigate future injuries from taking place. The Right Fitness Level Greater fitness leads to a better understanding of your limits, as well as the ability to achieve greater feats. A physical assessment by a good therapist or strength and conditioning coach can help you sort through the thousands of exercises out there to know which ones are relevant to your needs. - Slow, gradual increases in exercise and specific training are necessary (months and/or years). Our bodies adapt well to gradual stresses, but if too much load is placed on it at once, expect failure and injuries. It takes great dedication to yield great results. Most outdoor athletes peak in their 30s and 40s as they build cardiovascular endurance, muscular endurance, and a resistance to injury. - Outdoor athletes often suffer overuse / over-training. It is important to consider whether you have proper body mechanics during training and outdoor pursuits. Have knowledgeable therapists, coaches and other athletes watch your form and provide suggestions. It is also important to include adequate cross-training, regular body maintenance (physiotherapy, massage, rolling), proper nutrition, and adequate rest. - As a general rule there are certain joints which must be stable (strong ligamentous and muscular support around the joint, which prevents excess joint motion) and others which must have good mobility (the joint is built to be very flexible, however the muscular support around the joint must be able to control this increased range). As pertaining to lower body exercise, the core must be stable, hips must be mobile, knees must be stable, and the ankles must be mobile (Cook, Burton & Kiesel, 2010). Try adding the following 20-minute routine into your regular workouts, three days a week. It is a small corrective exercise program built to help the user become more aware of hip / knee / ankle positioning during single leg stance. It is not meant to replace regular strength training. Rather, it should enforce the principles of joint alignment, feeling posterior chain engagement and will allow good transfer to outdoor pursuits. A) Dynamic stretching. Perform dynamic stretching prior to exercise for 30 seconds per muscle group. A few lower body ideas include front/back and side-to-side leg swings, quick quadriceps stretches, quick piriformis/glute stretches, and hopping. B) Airplane. At first you may need to hold onto something for balance, but eventually you should be able to progress to no hands. Goal = 10 reps per side. C) Step-ups. Face a mirror and line up the hips and knees on the working leg to be approximately 90 degrees. Ensure that during the exercise, your knee tracks straight (not allowing it to collapse inwards or outwards). Lean forward, try to feel your glutes and hamstring fire on the upper leg then push through the heel on the working leg as you step up (this will help you to activate the posterior chain). Goal = 10 reps per side, with 2 times the expected weight of your backpack and gear. D) Single leg star balance. Reach as far in each of the four directions as possible, while bending the stance leg at the hip and knee during the reaching phase (this leg should remain straight in line from the hip to the foot). Goal = 10 reps for each leg. 1 rep = a full cycle of the four directions. Side note: Work to create symmetry in this test, as evidence suggests that a difference of more than 4 cm between left and right legs in ‘the forward reach’ component can help predict whether an athlete is at risk of injuring the leg (Smith, Chimera & Warren, 2014). Tip: Place masking tape on the ground and mark the distance in centimeters. E) Piriformis rolling and pigeon stretch. 1 minute rolling, 1 minute stretch per side. F) Lateral Quadriceps rolling and stretch. 1 minute rolling (focus on the outside of the leg), 1 minute stretch per side.

|

| Start With The Right Intel - Create specific training goals: How many days/hours, what gear do I need to use, am I familiar with the terrain? - Become efficient and effective in your skill-set by learning the best decision making skills and techniques via free resources (friends, books, videos), and progressing to courses or hiring a guide. | The Right Gear - Hiking poles take up to 25% of stress off your knees during descent (Schwameder, et al., 1999) help your legs save energy, and improve your balance on technical terrain. - Boots that fit well can prevent crushed toes, and rolled ankles. - Bring microspikes, mountaineering gear and/or avalanche gear if you expect snowy conditions. |

References

Schwameder, H., Roithner, R., Müller, E., Niessen ,W., Raschner, C. (1999).

Knee joint forces during downhill walking with hiking poles. Journal of Sports Science, 17(12): 969-978.

Smith, C.A., Chimera, N.J., Warren, M. (2014). Association of Y balance test reach asymmetry and injury in division I athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. Epub ahead of print.

Warning Signs

Some examples of objective signs may include changes (over the last week(s) / month(s) / year(s) in:

(1) Range of motion (ROM)

Has there been a change in your active or passive ROM? Does the end-feel of the last few degrees of your ROM feel the same as it always has? (i.e. does it feel like a muscle stretch, bone-on-bone, tissue approximation?

(2) Coordination

Can you perform simple and complex movement skills as easily as before? Are your movements performed with precision?

(3) Strength

Have you noticed any changes in your ability to access your muscle strength, endurance or power?

(4) Speed

Are you able to move as quickly in different movement patterns as before? Do you fatigue more easily?

(5) Symmetry

Are you able to control the left side of your body as well as you are on the right? Do your movements look symmetrical on both sides when you perform them in front of a mirror?

Some examples of subjective signs may include:

(1) Lack of confidence

Do you feel an incapability to execute the skill well? Does something just feel "off"? The skill may look well coordinated but may just feel uncoordinated.

(2) Poor decision-making when performing a skill

Are you able to make tactical decisions about using the skill? While performing a skill, are you able to make decisions regarding your environment to determine what your next course of action should be?

(3) Inability to multitask

Do you find it more difficult to talk (or do any number of other skill-sets) while you perform a skill?

(4) Poor body language

Do you feel awkward performing a skill that you used to be proficient in performing? Do other people seem to smile or chuckle while you perform the skill?

(5) Validated outcome measures

These outcome measures may help provide the patient with some insight into tasks they perform in their life that are difficult for them to do, even if they do not perceive symptoms to be present. This helps to create self-awareness. (Outcome measure examples include: Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, Upper Extremity Functional Scale, Upper Extremity Functional Scale, etc.)

Onset of Symptoms

Your liberation from the symptoms will result from:

(1) Determining the root cause of the injury.

(2) Fixing the problem before permanent damage occurs.

(3) Learning from it and becoming more aware of your body.

(4) Developing more strength and coordination than before to prevent a similar injury from reoccurring.

(5) Gradual return to the sports / activities you enjoy.

Concluding Remarks

Author

Jacob Carter lives and works in Canmore, Alberta. He combines research evidence with clinical expertise to educate other healthcare professionals, athletes, and the general public on a variety of health topics.

Archives

November 2022

July 2022

January 2022

February 2020

May 2019

April 2019

July 2018

May 2018

March 2018

January 2018

October 2017

September 2017

March 2017

February 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

May 2016

March 2016

January 2016

June 2015

February 2015

December 2014

October 2014

September 2014

Categories

All

Aging Population

Annual Check Up

Annual Check-up

Annual Physiotherapy Assessment

Calgary

Canmore

Climbing

Collaborative Care

Concussion

Core Muscles

Disease Prevention

Exercise

Exercise Selection

FDN

Frozen Shoulder

Functional Dry Needling

Health

Health Promotion

IMS

Inflammation

Injuries

Injury Prevention

Intramuscular Stimulation

Jacob Carter

Literature Review

Lumbar Spine

Manual Therapy

Mountaineering

Pain

Personal Training

Physiotherapy

Preventative Medicine

Rehabilitation

Research

Shoulder Impingement

Shoulder Injuries

Skiing

Ski Injuries

Ski Season

Swelling

Tendinopathy

Tendinosis

Tendon

Tendonitis

Trail Running

Wellness

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed