|

Recovering from an injury can be a nuanced process - there are some symptoms that you should listen to and others that aren’t so important, poor information abounds during searches on Dr. Google, there are friendly recommendations to try certain products, drugs or stretches, and just when you think it is okay to resume your normal activities pain may re-surge. It can be confusing… That being said, if you focus your attention on the overarching principles of an effective rehab, recovery doesn’t have to be complicated! Here are few key areas that anyone can assess and will help to simply your return to wellness: 1. Time A) If you’ve sustained an injury, rehab will take time. Determining its severity can help you plan your rehab timeline. If it’s a small injury (micro-tearing or grade 1 sprain/strain), allow three days of relative rest for the injured area and slowly start to return to your sport. If it was a moderate or severe injury (grade 2-3 sprain / strain, fracture), you will need more time to allow the injury’s wound margins to heal back together. Due to the magnitude of a more severe injury you will likely benefit from a support (see below) and clever ways of modifying activity/programming. B) If you are not seeing many signs of improvement from your injury within a week, consulting a health care provider (Physio/Doctor) is a good idea. Diagnosing the injury and its severity will be important for your rehab strategy and long-term success. 2. Exercise A) Make sure that you perform exercises specific for your injury/dysfunction. Your exercises should address all three of the following:

3. Supports A) Your recovery from an injury may be uncomfortable but it needn’t be exquisitely painful. Utilizing walking aids (crutches/cane/walking poles), braces, taping techniques, medication (oral, topical or injections) or certain types of shoes/orthotics may help to alleviate some of your pain. These supports are not be relied on for very long, but can help reduce the harmful effects of feeling too much pain during your recovery. 4. Activity level A). Many of my clients see me because they have slow progress or are seeing no progress. This is often because #2 is not being addressed and clients are often doing too much or too little activity in their day to day life. Determining the appropriate amount of activity requires:

Concluding Remarks Creating a good rehab program is an art. Of course there are other items to consider whilst recovering from an injury, but if you can dial in these four key areas it should help with setting realistic expectations and executing a planned recovery.

As always, if you have any questions feel free to send me an email or leave a comment!

2 Comments

Although I've taken several courses that address concussion assessment and treatment over the last few years, research is continually advancing our knowledge of guidelines. Here is a summary I've put together of some of the most recent literature which aims to answer the questions: Which patients require concussion rehabilitation and what does recent evidence suggest that concussion rehabilitation should include? Assessment and Treatment Timelines The most recent International Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport (The Berlin Consensus Statement, April 2017) states that evidence-based treatment for persistent concussion symptoms includes cervical spine treatment, vestibular rehabilitation, psychological interventions, and controlled submaximal exercise (1). The diagnosis of a concussion is a clinical judgment, made by a medical professional (1). A multi-faceted treatment approach seems to be the most effective approach to rehabilitation, and should begin immediately by obtaining a comprehensive history, performing a neurological exam to rule out serious pathology related to traumatic brain injury (TBI) or vascular insufficiency, and screening the cervical spine for signs of trauma. As a minimum, the health care team involved in the patient’s care should include a Family Physician and/or Sports Medicine Physician, and a Physiotherapist trained in concussion management. As required, patients may also benefit from a referral to see a psychologist, optometrist or dietician trained in concussion management. Recent evidence suggests that starting rehabilitation as early as 10 days after injury improves recovery time and decrease the risk of developing post-concussion syndrome (PCS) (2). For individuals with PCS, a multifaceted assessment is needed to identify targeted treatments that may be of benefit (3). Cervical, Vestibular, and Oculomotor Rehabilitation The amount of force necessary to sustain a concussion is far greater than that which is needed to sustain a whiplash (4). As a result, nearly every concussion sustains a whiplash as well. The significance of this fact is that whiplash injuries can disrupt the vestibular system (causing dizziness and vision dysfunction), result in cervical joint and muscle tightness/inflammation (causing local pain, referred headaches, and contribute to a lack of concentration), and disrupt the reflexes between cervical-vestibulo-occular system. In 2014, Schneider et al., published one of the first randomized clinical trials comparing a group receiving a combination of cervical and vestibular rehabilitation versus a control group that was given the usual protocol of rest followed by gradual exertion. Both groups received treatment from a physiotherapist at least once per week for 8 weeks, and had an average age of 15 years. In the treatment group, 73% of the participants were medically cleared within 8 weeks of initiation of treatment, compared with 7% in the control group. Individuals in the treatment group were 3.91 (95% CI 1.34 to 11.34) times more likely to be medically cleared by 8 weeks (2,5). In 2017, Reneker et al., published another randomized clinical trial comparing individualized treatment plans consisting of manual therapy of the neck, vestibular rehabilitation, oculomotor and neuromotor retraining, to a control group. Subjects were permitted by a sports medicine physician to enroll in the trial if they had experienced concussive symptoms for at least 10 days, and were treated by a Physiotherapist for up to a maximum of 8 visits or until they were fully cleared to return to play by a blinded sport-medicine physician. The progressive treatment group achieved symptom resolution and clearance to resume full sport activities significantly sooner than the control group: 15.5 days versus 26 days, respectively. The authors concluded that a personalized treatment plan beginning as early as 10 days after concussion may be an effective option to shorten recovery time (6). Exercise Recommendations Post-Concussion Initiating physical activity within the first 7-14 days post-concussion has been associated with a decreased risk of developing PCS. These results have been noted in adolescents and adults (7-12). Several clinical trial have demonstrated significant improvements in symptoms, cerebral blood flow mechanics, and complete return to all pre-injury activities over a much faster timeline compared to control groups or sham therapies (i.e. stretching). This is true for both acute concussions and PCS (7-10). Research would suggest performing low-level aerobic exercise most days of the week, at 80% of their symptom-tolerated heart rate (13,14). Summary: Providing Effective Treatment In addition to a graduated ‘Return to Learn’, ‘Return to Work’, and/or ‘Return to Play’ protocol, patients recovering from concussions seem to benefit the most from specific therapies for the cervical spine, vestibular system, visual system, and cardiovascular system. Research suggests that focused rehabilitation that begins within the first 7 to 10 days after injury can significantly improve outcomes and decrease long-term symptoms in both children and adults. References 1) McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, Aubry M, Bailes J, Broglio S, Cantu RC, Cassidy D, Echemendia RJ, Castellani RJ, Davis GA. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Apr 26:bjsports-2017.

2) Schneider K, Meeuwisse W, Nettel-Aguirre A, Boyd L, Barlow KM, Emery CA. Cervico-vestibular physiotherapy in the treatment of individuals with persistent symptoms following sport-related concussion: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2014 May 1;48:1294-8. 3) Feddermann-Demont N, Echemendia RJ, Schneider KJ, Solomon GS, Hayden KA, Turner M, Dvořák J, Straumann D, Tarnutzer AA. What domains of clinical function should be assessed after sport-related concussion? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jun 1;51(11):903-18. 4) Marshall CM, Vernon H, Leddy JJ, Baldwin BA. The role of the cervical spine in post-concussion syndrome. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2015 Jul 3;43(3):274-84. 5) Schneider KJ, Meeuwisse WH, Barlow KM, Emery CA. Cervicovestibular rehabilitation following sport-related concussion. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Jan 1;52(2):100-1. 6) Reneker JC, Hassen A, Phillips RS, Moughiman MC, Donaldson M, Moughiman J. Feasibility of early physical therapy for dizziness after a sports‐related concussion: A randomized clinical trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017 Dec 1;27(12):2009-18. 7) Baker JG, Freitas MS, Leddy JJ, Kozlowski KF, Willer BS. Return to full functioning after graded exercise assessment and progressive exercise treatment of postconcussion syndrome. Rehab Res Pract. 2012. 8) Leddy JJ, Cox JL, Baker JG, Wack DS, Pendergast DR, Zivadinov R, Willer B. Exercise treatment for postconcussion syndrome: a pilot study of changes in functional magnetic resonance imaging activation, physiology, and symptoms. J Head Trauma Rehab. 2013 Jul 1;28(4):241-9. 9) Gagnon I, Grilli L, Friedman D, Iverson GL. A pilot study of active rehabilitation for adolescents who are slow to recover from sport- related concussion. Sci and J Med Sci Sports. 2015; 26(3):299–306. 10) Imhoff S, Fait P, Carrier-Toutant F, Boulard G. Efficiency of an active rehabilitation intervention in a slow-to-recover paediatric population following mild traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. J Sports Med. 2016. 11) Lal A, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Ghajar J, Balamane M. The Effect of Physical Exercise after a Concussion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017 Jun 1. 12) Zemek R, Grool AM, Aglipay M, Momoli F, Meehan WP, Freedman SB, Yeates KO, Gravel J, Gagnon I, Boutis K, Meeuwisse W. Relationship of early participation in physical activities to persistent post-concussive symptoms following acute paediatricpediatric concussion. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jun 1;51(11):A20. 13] Schneider KJ, Leddy J, Guskiewicz K, Seifert TD, McCrea M, Silverberg N, Feddermann-Demont N, Iverson G, Hayden KA, Makdissi M: Rest and specific treatments following sport-related concussion: A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Mar 24, 51:930-4. 14) Leddy JJ, Kozlowski K, Donnelly JP, Pendergast DR, Epstein LH, Willer B. A preliminary study of subsymptom threshold exercise training for refractory post-concussion syndrome. Clin J Sport Med. 2010 Jan 1;20(1):21-7 While manual therapy and education may play a crucial role in injury rehabilitation, injuries and pain respond the best in the long-term to progressive loading through exercise. In fact, exercise is said to be "the closest thing to a miracle cure" (1), and is widely accepted as the means through which you can attain complete recovery. Prescribing exercise can be intimidating for some therapists, so I wanted to provide some facts and guidelines that may help make this easier! Fitting the Diagnosis to the Injury Attaining an accurate diagnosis CAN be difficult, but is often the first stage to developing a treatment plan, including exercise. 1. Do we know the actual pathology/diagnosis? An over-reliance on imaging and unreliable ‘special’ tests may mean that the true pathology (AKA reason for the client’s pain) may not fully be understood. A) Imaging typically looks at the injury site at a specific moment in time. To develop a true understanding of the pathology, this information must be examined along with the patient's subjective history and movement patterns. A common example in knee pain would be that an x-ray finding of moderate osteoarthritis of the patella is an additional finding, when the true reason for the patient's knee pain is trigger points in the quadriceps caused by suboptimal movement control. B) Many Special Tests are not that special. A special test should look to confirm suspicions of a specific diagnosis - they should not be used initially when developing a diagnosis. We know that many special tests lack sensitivity and specificity, and as a result are not helpful in confirming the diagnosis (even with a proper history and objective exam). Nicklaus Biederwolf, a physiotherapist and researcher, has this to say about special tests specific to the shoulder: "A great lack of consistency with regard to how, when, and what special tests to use in clinical examination for shoulder differential diagnosis is evident" (2). C) Different health care practitioners may develop different diagnoses that fit the information gathered during their assessment, and their bias. It is important to do a comprehensive assessment (including the client's previous medical history, mechanism of injury, pattern of pain, global movement patterns, and a specific joint/tissue/nervous system/vascular assessment). 2. Without imaging, we depend on clinical patterns to develop an accurate diagnosis, however similar pathologies may behave differently in the clinical setting. For example a partial thickness supraspinatus tear (one of the shoulder's rotator cuff muscles) may behave differently in one client versus other clients - and this may be for a wide variety of reasons: A) Anatomical variations: The acromion (a protrusion on our shoulder blade, under which the supraspinatus tendon glides) come in all shapes and sizes. The same applies to the rest of our bones, and muscles/tendons in our body - we are not as symmetrical and standardized as you may think! B) Regional Interdependence: Canadian Physiotherapists are known as 'The Movement Specialists' (3), so keep connecting the dots to determine how one area of the body may be affecting another! The thoracic spine, neck, scapula and all of its connecting muscles and ligaments alter the dynamic control and posture of the shoulder, which ultimately impact the supraspinatus tendon. C) Variations in nociception (sensing pain): Fewer pain nerve endings near the injury site, previous injury to nerve or blood supply at the area, or differences in central nervous system perception of pain on a global level will affect how a patient feels potentially harmful stimuli. D) Multiple injuries: A mechanism of injury that may tear the supraspinatus may also injure other tissues in the area. For example, there could also be an injury of the labrum, chondral surface of the humerus, biceps tendon, pec major, or subacromial bursa. It is nearly impossible to identify/distinguish all of these pathologies in the clinic without imaging... BUT does it really matter? Read on! What To Do.. in a World of Unknowns? It can all get quite confusing.. The items above paint a muddled picture: It can be quite difficult to come up with the correct diagnosis due to many(!!!) factors. Luckily, despite this fact, there are a few things we can do that will promote successful recovery. 1. It may be more important to focus on movement deficits first. Our bodies are exceptional at healing themselves. In fact, the best athletes in the world are the ones that recover the quickest (from training, games, or injuries). Most of the time, the injured tissue will heal on their own, but will leave us with tight muscles and poor movement patterns as a result of compensation. This means that pursuing imaging and specialist appointments may just end up being a waste of time, health care dollars, and stress. To start, the patient shoulder obtain a couple of opinions (physician and physiotherapist) to determine whether medical testing may be needed. Following these opinions, it is usually best to focus on improving flexibility and movement control. 2. Zoom out; Broaden your perspective! Often we warn patients against performing certain exercises, based on the fact that they have a certain pathology (e.g. with an acute partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon, stay away from dips or deep bench press). Take a step back and look at global movement patterns - are there any other restrictions / dysfunctions that you could work on first? In our case example: Do you need to work on thoracic mobility, activating scapular upward rotators, releasing scapular downward rotators, activating deep neck flexors, releasing posterior rotator cuff, releasing adhesions at the interface of pec major / supraspinatus / long head of biceps? Maybe a further step back would even suggest asymmetries in lower body, lower back, or neck strength/mobility. 3. Prescribing the exercise. Suggesting that the patient does a specific exercise is not enough. Ensure that the correct exercise is performed correctly; Spend time on coaching form and don’t expect that your client knows how to do the exercise properly. Lastly, discuss the importance of correct exercise: 1. Volume 2. Intensity 3. Rest 4. Tempo By changing these four variables, we can ultimately train the tissue work for its intended purpose and improve A) Muscular endurance B) Muscular power C) Muscular reactivity (plyometrics) D) Tendon loading capacity 4. Test, and Re-Test If you've taught the exercises well, allow adequate time for a beneficial result to occur, and re-test the client's functional deficits. 5. Lastly, a client’s most effective exercises may change overtime due to movement quality, tissue quality, perceived effort/challenge, ability to recover quickly, or the applicability to sport and life specific challenges. Follow up a few weeks or months down the road to provide the best possible care to your client. References (1) Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Exercise: The miracle cure and the role of the doctor in promoting it. AOMRC.org.uk. 2015 Feb

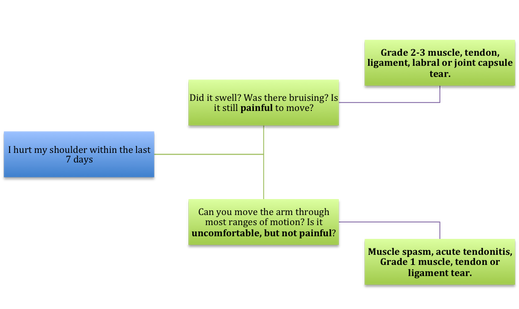

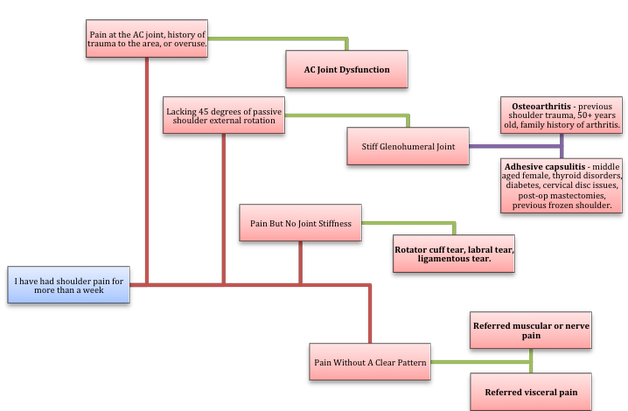

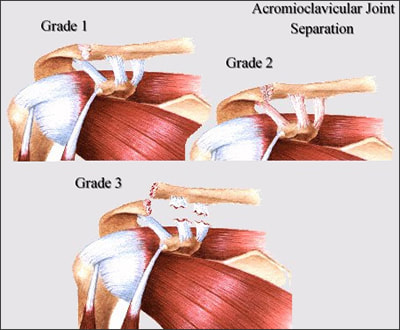

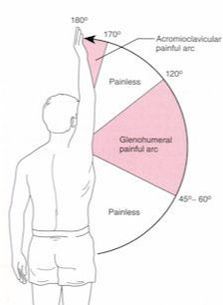

(2) Biederwolf, Nicklaus E. "A proposed evidence-based shoulder special testing examination algorithm: clinical utility based on a systematic review of the literature." International journal of sports physical therapy 8.4 (2013): 427. 3) Physiotherapy Alberta: About Physiotherapy. Accessed February 1, 2018. https://www.physiotherapyalberta.ca/public_and_patients/about_physiotherapy If Only Our Bodies Came With User Manuals! It's tough to know when its okay to push through pain or stiffness, or to know if the recent shoulder tweak that happened last week is of any importance. Over the last number of years I've picked up a number of strategies from research and experts in the sports medicine and orthopaedic world - I hope this can serve as a general guide! (NB - this is a blue print for simple shoulder injuries, and will not fit every situation. Use the following information as the guide that it is, and seek additional advice if you need further guidance!) Did You Hurt Your Shoulder Within The Last 7 Days? To start it off, if you've hurt your shoulder in the last 7 days, read through the following flow chart, and then the corresponding text below: Grade 2-3 muscle, tendon, ligament, labral or joint capsule tear If you experience significant pain, possibly with swelling or bruising, it is likely that you have significantly injured your soft tissues. While outliers exist (bone fracture or nerve involvement), it is most likely an issue related to a tear of a muscle, tendon, ligament, or the joint structure, If the pain in significant, a trip to the ER or family doctor may be the best first option. In terms of rehabilitation, it is probably best to let the shoulder heal for at least 7 days from the initial injury date before starting active rehab exercises. During this time you should see your local physiotherapist or sports medicine physician for an accurate diagnosis and to develop a treatment plan. During the first 7 days, you can support the shoulder with tape or a sling, apply ice (if you need to numb the pain), and perform pain-free range of motion. You should continue to exercise your lower body during this time. You can reasonably expect that there will be a range of motion limitation and/or strength reduction for at least 3 weeks from the date of the injury. It would be advisable to avoid loading the injured tissues with exercise for at least 3 weeks as the injury heals. As per standard tissue healing timelines, the injured tissues will not reach their full strength for up to 9-12 months in a healthy adult… so it is important that you do not re-injure it in the first 3-6 months (to be conservative). Muscle spasm, acute tendonitis, grade 1 muscle, tendon or ligament tear. If you've come to the conclusion that it's likely a muscle spasm, or minor muscle strain / ligament sprain, start immediately with soft tissue release, foam rolling, and gentle stretching into the areas of tightness. Within the first 3-7 days, start to do some light and pain-free resistance exercises to the surrounding muscles (e.g. easy rotator cuff exercises with a theraband). By the end of week 2 you should have loosened up most of the muscle tightness around the shoulder, and should be starting to gradually increase load/exercise for the shoulder. If your discomfort and limited range of motion is not gone within the first 2 weeks, get it assessed and treated. These small nagging injuries have a way of accumulating over the years and may predispose you to a more severe problem in the future. Have You Had Shoulder Pain For More Than 7 Days? This becomes more complicated as we have to discern between a number of different potential concerns. Acromioclavicular (AC) joint dysfunction - There are a few differed reasons that you may develop AC joint dysfunction. First, and most simple, is a direct hit to your shoulder. You will remember this happening, so in this case, its not too complicated. You will likely experience pain and joint laxity when you press on the AC joint, and in severe cases you may experience a 'separated shoulder' that looks like this: The good news about separated shoulders is that physiotherapy (as opposed to surgery) is often enough to help athletes and recreationalists return to their sports and daily activities pain free. If you do not remember a direct trauma, the following may apply to you: The AC joint is often the site of arthritis and come on from overuse or impact (most often seen in athletes (hockey, football, baseball, weight lifters, or overhead work). Pain and dysfunction from the AC joint often can cause impingement of the rotator cuff, and as such may present with muscle weakness, pain down the arm as far as the elbow, and a painful arc of motion. The symptoms that you experience during the arc of motion can help differentiate if it is just the joint that is irritable, or if there may be a rotator cuff impingement; If you have pain between 45-120 degrees abduction, but no pain before or after this range, then it is likely that you have an impingement of supraspinatus muscle (with or without an inflamed bursa). If you only have pain at the very top of this range of motion, it is likely that your AC joint is irritable. Assessment-informed treatment is often the key if it is a chronic pain: 1) You may benefit from other tests that can be done by a physiotherapist to assess joint integrity. 2) An X-ray may be of benefit to ensure there is no bone spur or congenital abnormality of the acromion, 3) A diagnostic ultrasound may be helpful to discern whether the supraspinatus tendon or subacromial bursa are irritated. Conservative treatment is the first-line treatment, as you will almost certainly have tightness and weakness of the surrounding shoulder musculature which may be causing secondary pain. A good assessment is usually needed to assess and treat the neck, thoracic spine, scapulothoracic rhythm, sternoclavicular joint mobility, scapulohumeral rhythm, and the AC joint. Most importantly, returning to a quality, pain-free exercise program will quicken the recovery. Differentiating Reasons for a Stiff Shoulder JointOne of the easiest ways to assess a stiff joint, is to look at passive range of motion, and try to assess the end-feel of the motion. If you are lacking 45 degrees of passive shoulder external rotation, and it feels like there is a capsular or joint restriction (hard end-feel), you likely fit into this category. Often, these cases require a medical approach to rule out other pathologies - be prepared to seek a referral to your family doctor or sports medicine physician for some imaging (to rule out sinister pathology or rule in arthritis), or blood work.  To assess passive shoulder external rotation, lay down on your back, and with you painful arm completely relaxed, use a broomstick or cane to gentle push the painful arm outwards (rotating the shoulder out). Keep your elbow relaxed and next to your ribcage. Remember... you are trying to assess the stiffness of the joint, so all muscles in the painful arm must remain relaxed! Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis If you have had a previous shoulder trauma, are 50+ years old or have a family history of arthritis, the most likely problem is that of glenohumeral osteoarthritis (could be from previous instability, or because of normal wear and tear associated with age). Manual therapy that focuses on improving joint capsule mobility is often required to make progress. Various joint injections exist that may help with lubrication of the joint, or inflammation within the joint. At home, patients can start with rolling tight muscles on the back of the shoulder joint to loosen any tissues that may be restricting the joint mobility. Ultimately, most progress will be made with the help of physiotherapy or medical intervention. Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder) The most likely alternative reason for a stiff shoulder is adhesive capsulitis. The strongest risk factor for developing adhesive capsulitis is being a peri-menopausal female. Other risk factors include thyroid disorders, diabetes, cervical disc issues, post-op mastectomies, a recent fall/trauma, and having a previous frozen shoulder. The shoulder seems to stiffen and become painful without a usual cause, and keeps patients awake at night. We see patterns of limited external rotation, internal rotation and flexion. If the diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis is reached, patients may find a cortisone injection helpful in the early stages. There has also been some clinical evidence showing that manipulation of the fibrotic joint under a nerve block may be of benefit.. Otherwise, regular physiotherapy that includes stretching, shockwave therapy, and manual therapy (soft tissue release, IMS, and joint mobilizations) will provide the greatest benefit. Shoulder Pain with Limited Active Range of Motion but Without Joint Stiffness If you do not have a stiff glenohumeral joint (more than 45 degrees passive external rotation), yet there is shoulder pain and limited active range of motion, a skilled practitioner will take you through a number of tests to help determine whether the pain is coming from a rotator cuff tear, labral tear or ligamentous tear (this is usually preceded by a dislocation / subluxation). The diagnosis of a tear must be ascertained by the clinic history, movement exam, special tests, response to treatment, and possibly ultrasound/MRI/other imaging. For the purposes of this article I am going to avoid the discussion of which special tests may be useful for diagnosing tears; This is a contentious issue as most special tests are... not that special; they are not very specific toward testing just one tissue and often lead to false positives. This topic is beyond the scope of this article. Shoulder Pain Without a Clear Pattern Very few patients fit into this category, so if you think that you do, its likely that you've missed something during your self-assessment. Excluding this caveat, I write this last section for completion. 1. Referred Pain - A painful shoulder that has no pattern of painful movement may be experiencing referred symptoms from the neck, diaphragm or the heart. 2. Cancer/Metastases - A number of different viscera can create pain into the shoulder region. Most likely include the lung, liver, and gallbladder. Typically you will experience unrelenting pain (nothing can make the symptoms change), difficulty sleeping at night, excessive fatigue, weight loss, a fever, or any number of other changes in your normal health. See the following link for more information: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-basics/signs-and-symptoms-of-cancer.html 3. Pain Syndromes - Widespread hypersensitivity/hyperalgesia may also affect the shoulder. Various non-specific pain syndromes may create shoulder pain and include: Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome, Myofascial Pain Syndrome & Fibromyalgia. A Final Note In most cases of shoulder pain, an exercise program is the key component necessary to return to full function without pain. In cases of partial thicken tendon tears, full thickness tendon tears or subacromial impingement, a specific and progressive exercise program often provides improved function, reduced pain and reduced need of surgery when compared with a general exercise program (1, 2, 3). My typical progression in the clinic is: 1) Determine if patient has any red flags that indicate immediate medical assessment / intervention. 2) Assess full body movement to determine how one area of the body may be affecting another. 3) Assess the shoulder for joint integrity, ligament and tendon damage, flexibility and strength. 4) Perform manual therapy, IMS and shockwave (if needed) to reduce pain and improve joint position/posture. 5) Provide patient with a specific, graduated exercise program. 6) Assess progress of the shoulder and repeat 2-6 as indicated until full function is .recovered, or a referral is indicated to see a sports medicine specialist. References (1) Björnsson Hallgren, H. C., Adolfsson, L. E., Johansson, K., Öberg, B., Peterson, A., & Holmgren, T. M. (2017). Specific exercises for subacromial pain: Good results maintained for 5 years. Acta Orthopaedica, 1-6.

(2) Holmgren, T., Hallgren, H. B., Öberg, B., Adolfsson, L., & Johansson, K. (2012). Effect of specific exercise strategy on need for surgery in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: randomised controlled study. Bmj, 344, e787. (3) Kukkonen, J., Joukainen, A., Lehtinen, J., Mattila, K. T., Tuominen, E. K. J., Kauko, T., & Äärimaa, V. (2014). Treatment of non-traumatic rotator cuff tears. Bone Joint J, 96(1), 75-81. Consistent Training Leads to Skilled Running Most athletes will attest that consistency is the most important aspect in progressing fitness and skill through training. This is why injuries set you back from reaching your full potential, or at least reaching goals in a timely fashion. While running, there are many things we can do to prevent injuries and some of them require very little time to implement, although learning the most effective way to implement them is individualized and may take years to achieve personal efficiency. Indeed, running is a skill, and it takes a long time to learn how to use your body in the most effective way. With a good training plan you will improve your efficiency, which will reduce physical and mental fatigue, reduce injury risk, and ultimately improve your performance! If you are new to running, or are simply wanting to improve, try these movement tweaks the next time you head out the door. N.B . These tweaks are good guidelines, but if you have a preexisting dysfunction (remember a dysfunction may not present with pain or any other symptom), you may benefit from a personalized approach. If you fall into this group, book in for a running assessment or seek guidance from a running coach, or rehab professional with post-graduate training in running assessments. It's Much More Than One Foot in Front of The Other 1) Upright posture. "Be tall!" At the start of your run, and periodically during your run, remind yourself to be tall. Think about elongating your entire spinal column; That is... if you had a string attached to the top of your head that connects down through the middle of your body, think about pulling that string up! You should not dramatically change your spinal curve with this, but you should feel that you are slightly taller. Why? When done appropriately, this helps to engage your multifidus muscles (spinal stabilizers), and make you aware of your core. This will help prevent energy loss due to poor stability, and will better allow you to apply force through your hips - helping to propel you forwards. It also helps with diaphragmatic activation and reduces the amount of airway resistance during breathing. PS - it might be a good idea to start thinking about upright posture during the rest of your day, as we spend thousands of hours hunched over at work and at home each year, and BELIEVE IT OR NOT!, this affects our athletic performance! 2) Forward lean from the feet / ankles "Lean forward from the ankles!" Running should be efficient. Leaning forward from the ankles aids in this efficiency, because it moves your center of mass slightly forward, and allows you to fall into your next stride. Don't forget #1 - it is too easy to let your forward lean come from hinging at the hips - "Stay Tall", and keep your head up, as you need to be looking forward! 3) Posterior-chain propulsion "Push, don't pull!" If we lean forward from the ankles, we will fall forward and must flex our hip joint and extend our knee to "catch" us from falling on our face. We can use this forward energy most effectively by pushing ourselves forward, as soon as our foot hits the ground. Try to see if you can feel yourself pushing forward using your glutes, hamstrings and calves. 4) Shortened stride and increased cadence "Shorten your stride and increase your cadence!" "Imagine that you are a ball, and as you are rolling over the ground, you are attempting to touch as many different places on the ground as possible" Most research suggests that elite runners who stay injury-free run with a cadence between 160-190 BPM. In most runners this improves multiple metrics (decreased "breaking phase", decreased vertical oscillation, decreased need for force absorption), and ultimately it decreases the amount of wear and tear / abuse placed on joints and muscles. In addition, it is said to improve efficiency in the long-term after the athlete adjusts to running in this way. The best place for our foot to land is directly under our center of mass because it minimizes the "breaking phase". The breaking phase is best described as wasted energy in the time between the foot striking the ground, and the push off phase when we propel ourself forwards. To ensure that we land with a vertical tibia - it is crucial to having a high cadence and a shortened stride. 5) Land with your foot under your center of mass "Most often, you should land using a midfoot strike" The jury is still out on what the best type of foot strike looks like in endurance athletes, but here is what we do know: A) A midfoot strike is mostly likely to place the foot under your center of mass while running on flat ground. B) Landing with a forefoot strike lends to a 2.6 times decrease in injury risk compared to rearfoot strikers (1). C) Landing on the forefoot or midfoot places more stress on the foot musculature and Achilles tendon. Landing on the rearfoot places more compressive loading forces at the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints of the knee. C) Rearfoot strikers tend to land with their foot in front of the body, which leads to have a longer stride and greater vertical loading (increased forces applied to the body) (2). D) Wearing shoes with larger heels lends to heel striking, whereas taking shoes off leads to landing on the forefoot or midfoot, with the strike being closer to the body. As always, we are reminded that science has limitations and common sense prevails, therefore do what feels right... BUT my recommendation would be to run on variable terrain, AND: A) As you run uphill, strike with your forefoot or midfoot. B) As you run the flats, strike mostly with your midfoot. C) As you run downhill, midfoot or heel strike may be best. Concluding Remarks These are but a few ways to immediately change your running form, in an effort to improve efficiency and promote injury-free training. General recommendations are terrible because they assume that all people are alike, so make no mistake - it is probably best to have a running assessment done to determine whether you truly need to change your running form. Nevertheless, exposing yourself to learn different styles of running will grow your running skill-sets and your body's durability, ultimately making you a better athlete! References 1) Daoud, Adam I., et al. "Foot strike and injury rates in endurance runners: a retrospective study." Med Sci Sports Exerc 44.7 (2012): 1325-34.

2) Williams III, Dorsey S., Irene S. McClay, and Kurt T. Manal. "Lower extremity mechanics in runners with a converted forefoot strike pattern." Journal of Applied Biomechanics 16.2 (2000): 210-218. |

Have you found these article to be informative, helpful, or enjoyable to read? If so, please visit my Facebook page by clicking HERE, or click the Like button below to be alerted of all new articles!

Author

Jacob Carter lives and works in Canmore, Alberta. He combines research evidence with clinical expertise to educate other healthcare professionals, athletes, and the general public on a variety of health topics. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed