|

Recovering from an injury can be a nuanced process - there are some symptoms that you should listen to and others that aren’t so important, poor information abounds during searches on Dr. Google, there are friendly recommendations to try certain products, drugs or stretches, and just when you think it is okay to resume your normal activities pain may re-surge. It can be confusing… That being said, if you focus your attention on the overarching principles of an effective rehab, recovery doesn’t have to be complicated! Here are few key areas that anyone can assess and will help to simply your return to wellness: 1. Time A) If you’ve sustained an injury, rehab will take time. Determining its severity can help you plan your rehab timeline. If it’s a small injury (micro-tearing or grade 1 sprain/strain), allow three days of relative rest for the injured area and slowly start to return to your sport. If it was a moderate or severe injury (grade 2-3 sprain / strain, fracture), you will need more time to allow the injury’s wound margins to heal back together. Due to the magnitude of a more severe injury you will likely benefit from a support (see below) and clever ways of modifying activity/programming. B) If you are not seeing many signs of improvement from your injury within a week, consulting a health care provider (Physio/Doctor) is a good idea. Diagnosing the injury and its severity will be important for your rehab strategy and long-term success. 2. Exercise A) Make sure that you perform exercises specific for your injury/dysfunction. Your exercises should address all three of the following:

3. Supports A) Your recovery from an injury may be uncomfortable but it needn’t be exquisitely painful. Utilizing walking aids (crutches/cane/walking poles), braces, taping techniques, medication (oral, topical or injections) or certain types of shoes/orthotics may help to alleviate some of your pain. These supports are not be relied on for very long, but can help reduce the harmful effects of feeling too much pain during your recovery. 4. Activity level A). Many of my clients see me because they have slow progress or are seeing no progress. This is often because #2 is not being addressed and clients are often doing too much or too little activity in their day to day life. Determining the appropriate amount of activity requires:

Concluding Remarks Creating a good rehab program is an art. Of course there are other items to consider whilst recovering from an injury, but if you can dial in these four key areas it should help with setting realistic expectations and executing a planned recovery.

As always, if you have any questions feel free to send me an email or leave a comment!

2 Comments

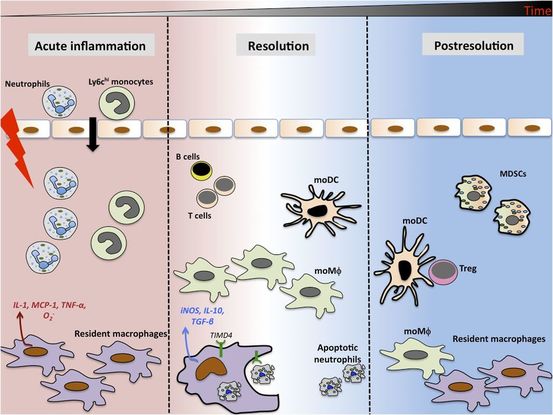

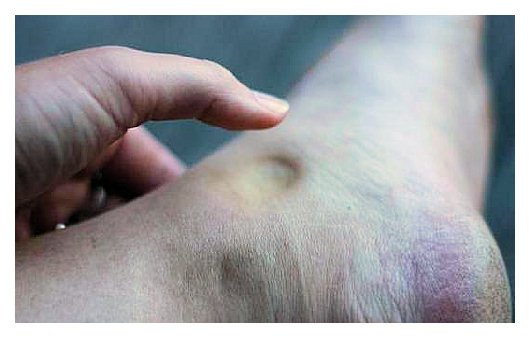

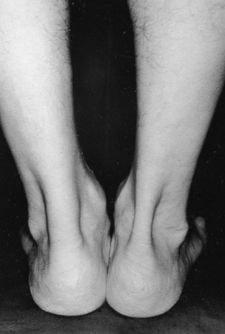

As written for www.one-wellness.ca We try to improve the body’s natural response to injury in many different ways. Health professionals around the world offer products and techniques that promise the greatest reduction in inflammation and swelling, believing that their product can rise above the competition… But why? Is it helpful to alter these responses, and is it even possible that we can alter these responses? For the most pragmatic answers, we can rely only on research… Definitions Understanding the differences in medical terminology allows us to better understand what processes are happening in our body. With this higher level of understanding, both practitioners and patients can better communicate what is happening in the body to achieve optimal outcomes. Swelling and inflammation of are often thought of as synonymous terms, however they have distinct definitions and applications. Inflammation: Inflammation is “a local response to cellular injury that is marked by capillary dilatation, leukocytic infiltration, redness, heat, and pain and that serves as a mechanism initiating the elimination of noxious agents and of damaged tissue” (1). Swelling: From Greek, the word ‘oídēma’ translates to ‘swelling’ (2). ‘Edema’ suggests “an abnormal infiltration and excess accumulation of serous fluid in connective tissue or in a serous cavity” (3). To briefly summarize, inflammation is a cellular response to tissue injury and may result in swelling, however swelling can actually occur within the body without the process of inflammation. A few common examples of swelling occurring within the body, in the absence of inflammation include: Lymphedema (failure of lymphatic drainage system to circulate blood plasma, and immune system regulators), cerebral edema (accumulation of extracellular fluid in the brain), pulmonary edema (accumulation of extracellular fluid in the lung). A few common examples of swelling that occurs within the body with inflammation as the causation includes: Acute tissue injury (fractures, sprains, strains), dermatitis (inflammation of the dermis layer of the skin), thrombophlebitis (inflammation of vein due to a blood clot). Treating Inflammation Is it possible to alter the inflammatory response? Is it helpful to alter the inflammatory response? Over the last few decades there has been a culture of reducing inflammation immediately following acute injuries. However recent research has been changing the way clinicians should treat acute injuries: Anti-inflammatory medication can decrease the inflammatory response, but they may impair healing: In addition to their potential side effects (affecting GI tract, kidneys and cardiovascular systems), using NSAIDs (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) may result in: a) Impaired bone healing after a fracture (4-9). b) Impaired tendon healing after an acute injury (10-11). c) No improvements in chronic tendinopathies, as there is no active inflammatory process (12). d) No improvement or possible small improvements in functional recovery In acute ligament injuries (13-18). Although one study found that using NSAIDs resulted in decreased pain and improved functional status, they also found a greater risk of adverse affects compared to using only analgesics. Also, one review of the literature found that acetaminophen is as effective as NSAIDs for pain reduction after musculoskeletal injury (19). These new results teach a few lessons: 1) The inflammatory mediators (e.g. prostaglandins, and cytokines) in inflammation help to initiate the subsequent stages of healing. 2) Removal of inflammation from an acute injury may harm the subsequent stages of healing. 3) In many cases, acetaminophen (e.g. Tylenol) will help to reduce pain as much as the use of anti-inflammatory medications, and will not impair healing. The overall justification for the use of the RICE principle (Rest, Ice, Compression Elevation) is very practical and helps minimize bleeding into the injury site. However, there has not been a single randomized, clinical trial to validate the effectiveness of the entire principle. 50 There is some support for each item, including immediate rest, and elevation to help in managing the accumulation of interstitial fluid (20). Summary: As much as possible restrict the usage of NSAIDs, employ the RICE principle, and if pain requires additional control then consider the use of other analgesic medications (e.g. acetaminophen, opiods, etc). It is a counterproductive goal to attempt to resolve all inflammation around the acute injury site. Treating Swelling Is it possible to alter swelling caused by acute injuries? Is it helpful to alter the swelling? It is possible to alter swelling that has been caused by acute injuries. In the following photos you can see that with appropriate rehabilitation, swelling improves. Unlike inflammation, it is in your best interest to reduce the amount of swelling at the local injury site. Depending on the amount of swelling, it can result in nerve compression, and restricted joint mobility making it painful and difficult to move the affected area (21). There is no benefit of allowing this swelling to stagnate as it will increase the level of irritability of the injury site and cause further deconditioning. While there are numerous modalities that purport to increase blood flow (e.g. interferential current, acupuncture, laser, ultrasound, etc., they majority lack substantial research and are unnecessary to resolve 99% of cases. In addition to the RICE principle mentioned previously, there are two supported methods to reduce swelling at the injury site: Movement - Regular movement of the affected joint, or at least the joints above and below should help pump the excess fluid back toward your heart using the lymphatic system. In addition, when able, start to perform cycling, swimming, rowing or perform upper body exercises. Massage - Stroking the affected area toward your heart using firm pressure may help move the excess fluid out of that area. There are many physiotherapists and massage therapists that have extra training in lymphatic drainage techniques that may be able to guide you, if you have been experiencing poor outcomes. References 1. Merriam-Webster Dictionary [Internet]. 2018. Inflammation; 2018-07-28. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inflammation

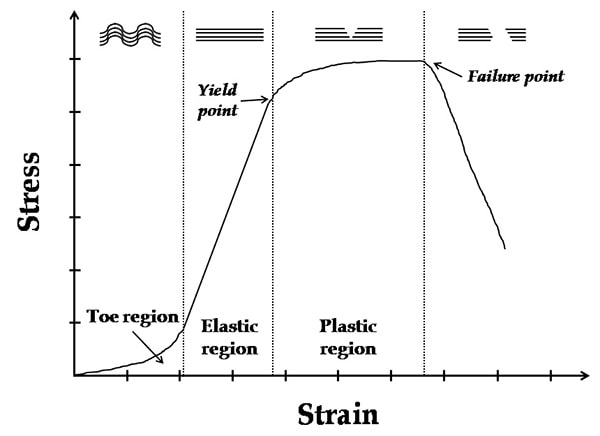

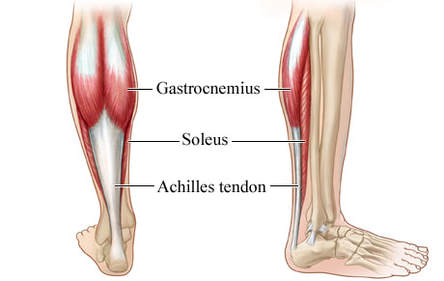

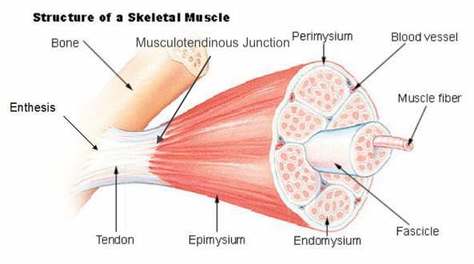

2. Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus 3. Merriam-Webster Dictionary [Internet]. 2018. Edema; 2018-07-28. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/edema 4. Matsumoto MA, De Oliveira A, Ribeiro Junior PD, et al. Short-term administration of non-selective and selective COX-2 NSAIDs do not interfere with bone repair in rats. J Mol Histol. 2008;39:381-387. 5. Endo K, Sairyo K, Komatsubara S, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor delays fracture healing in rats. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:470-474. 6. O’Connor JP, Capo JT, Tan V, et al. A comparison of the effects of ibuprofen and rofecoxib on rabbit fibula osteotomy healing. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:597-605. 7. Bergenstock M, Min W, Simon AM, et al. A comparison between the effects of acetaminophen and celecoxib on bone fracture healing in rats. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:717-723. 8. Giannoudis PV, MacDonald DA, Matthews SJ, et al. Nonunion of femoral diaphysis: the influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B:655-658. 9. Bhattacharyya T, Levin R, Vrahas MS, Solomon DH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and nonunion of humeral shaft fracture. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:364-367. 10. Elder CL, Dahners LE, Weinhold PS. A cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor impairs ligament healing in the rat. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:801-805. 11. Ferry ST, Dahners LE, Afshari HM, Weinhold PS. The effects of common anti-inflammatory drugs on the healing rat patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1326-1333. 12. Aström M, Westlin N. No effect of piroxicam on achilles tendinopathy: a randomized study of 70 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:631-634. 13. Lane LB, Boretz RS, Stuchin SA. Treatment of de Quervain’s disease: role of conservative management. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26:258-260. 14. Dahners LE, Gilbert JA, Lester GE, et al. The effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug on the healing of ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:641-646. 15. Moorman CT 3rd, Kukreti U, Fenton DC, Belkoff SM. The early effect of ibuprofen on the mechanical properties of healing medial collateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:738-741. 16. Ekman EF, Fiechtner JJ, Levy S, Fort JG. Efficacy of celecoxib versus ibuprofen in the treatment of acute pain: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial in acute ankle sprain. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2002;31:445-451. 17. Ekman EF, Ruoff G, Kuehl K, et al. The COX-2 specific inhibitor Valdecoxib versus tramadol in acute ankle sprain: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:945-955. 18. Slatyer MA, Hensley MJ, Lopert R. A randomized controlled trial of piroxicam in the management of acute ankle sprain in Australian Regular Army recruits. The kapooka ankle sprain study. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:544-553. 19. Feucht CL, Patel DR. Analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications in sports: use and abuse. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:751-774. 20. van den Bekerom MP, Struijs PA, Blankevoort L, Welling L, Van Dijk CN, Kerkhoffs GM. What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults?. J Athlet Train. 2012 Jul;47(4):435-43. 21. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s Principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. 18th ed; 2011. Basics of Tendon Function Tendons attach muscles to bones. Simple enough, right? Well... kind of... not really! Tendons are a specific type of force-transmitting architecture between a muscle and a bone. They are made of a strong fibrous collagen tissue and transmit the force of muscular contraction to a bone in an effort to create joint motion. Good quality tendons are like stiff springs; A stiff spring will stretch a little, and then recoil with most of the force that was required to stretch it initially. In our tendons, we call this stretch 'creep', and the recoil of the tissues 'recovery'. To prevent wasting energy and causing damage to a spring (or a tendon in this case), we need to have a certain degree of stiffness, resilience and efficiency. An example of this would be if I create tension in my calf by hopping on a single leg. The calf muscles transfer this fairly high load to my calcaneous bone via the achilles tendon. When I do this action repeatedly, a strong tendon will be able to handle the load that is asked of it... whereas a tendon with poor load tolerance may start to creep and not recover quickly... which means that some of the energy that was loaded into the tendon will be lost. This can lead to fatigue of the tissue, and eventually inflammation and micro or macrotearing of the tendon (small tears or a complete rupture). Peritendinous Dysfunction There are three common anatomical areas that lead to peritendinous dysfunction and pain: The weakest zones of a tendon are where it transitions from tendon to bone (enthesis), followed by the transition zone from muscle to tendon (musculotendinous junction) (1). Additionally, since tendons are mostly found near joints, they are protected from the hard bony surface by a bursa (a fluid-filled sac). If there is excessive compression of a tendon on a bursa, it will often become inflamed and irritable. This is more common than you'd expect, and often a diagnosed tendinopathy includes a bursitis. Creating Tendon Irritability Tendons become irritable when they are stressed beyond their load tolerance. Overuse may develop for one of many reasons: 1) Excessive volume: Tendons may not be able to adapt to an increased volume of a specific activity (over a period of days/weeks/months) 2) Poor biomechanics: Doing a motion differently than you may have done it previously (over a period of days/weeks/months) may cause irritability, even if the volume hasn't changed. If you've been doing a specific motion with poor biomechanics for a while, but then increase the volume, re-read principle #1. 3) Impaired mobility or strength elsewhere: Often, a proximal or distal impairment may cause you to (a) move poorly, which may ultimately cause you to over use some parts of your body and under-use others (b) compress on nerve tissues 4) Excessive stretching: Prolonged and frequent stretching of muscles/tendons may result in excessive creep and poor recovery of the tendon. Subsequent loading of the tendon may result in increased potential of tendon irritation. 5) Nerve compression: Decreased space at the intervertebral foramen (where the nerves exit your spine), or compression of a nerve by tight muscles may affect the strength of the muscles supplied by that nerve. This may cause poor movement patterns, referred pain, and /or dysfunctional muscle tone that may cause irritation of the tendon. 6) Maintenance required: Even with reasonable volume and good biomechanics, if you ask your body to perform an activity enough and don't ensure that the muscles maintain good mobility and tissue quality, the muscles may develop trigger points which in turn will pull on its tendon with increased tension. 7) Intrinsic factors: An individual's risk for developing tendinopathy is also affected by older age, sex, and systemic diseases such as Marfan's Syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome, thyroid disorders, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and having a predisposition to developing kidney stones, gallstones or gout(2). Changes on a Cellular Level Microtearing of tendon fibers will evoke a cascade of events, mainly in areas with poor blood supply: 1) Cytokines (small proteins that have an effect on the behavior of cells around them) activate tendon fibroblasts (cells that help to lay down type 3 collagen to help with the initial healing the cellular matrix that was disrupted). 2) At the same time, pain stimulating mechanisms are activated due to the inflammation that was created during the activity that damaged the tendon. 3) Other proteins in the area stimulate enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix (the support network for tendon cells), and promotes the formation of new blood vasculature and new nerves (3). The result is a thicker, yet weaker tendon. It has a greater density of nerve endings which increases the sensitivity to all stimuli including the chronic inflammation. Together, these factors create a positive feedback system in which the inflammation irritates the nerve endings, causing increased inflammation... AND the chronic inflammation degrades the quality of the tendon itself. This means that when the tendon is loaded during sports or daily activities, further injury will occur to the tendon, thus creating additional inflammation and pain (3).  When a tendon is loaded or stretched beyond the elastic range, it experiences irreversible creep (plastic changes) to the tissue. This is known as microtearing, and will eventually lead to collagen / scar tissue formation, resulting in tendon thickening. If it continues beyond the plastic phase, macrofailure (a complete tear) of the tendon may occur (4,5). Tendon Take-Homes Statistically significant increases in tendon strength can be seen in the research after approximately 2-3 months of consistent strength training. Conversely, in a prolonged period of deloading, it only takes between 2-4 weeks to see statistically significant decreases in tendon strength (6-8). Therefore, a few general principles can be gleaned from all of the above information: 1) Train regularly, and do not take more than 2 weeks off from strength training, or else you may face the consequences. 2) Gradually increase your training volume in anything you do that is physically active. 3) Correct the mobility restrictions, strength impairments, and poor movement patterns that are within your control. Have a good personal trainer, coach, or physiotherapist assess your movement patterns. 4) If you are using your body regularly, use a foam roller regularly (poor man's massage therapist), and see a body worker (e.g. massage therapist or physiotherapist) for maintenance visits (once a month minimum). 5) Control your modifiable risk factors for developing comorbid conditions: Eat (mostly) healthy, sleep (mostly) well, and live a happy and stress-reduced life. Stay tuned for my next article that will examine elbow tendinopathy and management strategies! References 1) Apostolakos J, Durant TJ, Dwyer CR, Russell RP, Weinreb JH, Alaee F, Beitzel K, McCarthy MB, Cote MP, Mazzocca AD. The enthesis: a review of the tendon-to-bone insertion. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2014 Jul;4(3):333.

2) Rees JD, Wilson AM, Wolman RL. Current concepts in the management of tendon disorders. Rheumatology. 2006 Feb 20;45(5):508-21. 3) Abate M, Silbernagel KG, Siljeholm C, Di Iorio A, De Amicis D, Salini V, Werner S, Paganelli R. Pathogenesis of tendinopathies: inflammation or degeneration?. Arthritis research & therapy. 2009 Jun;11(3):235. 4) Svensson RB, Hassenkam T, Hansen P, Magnusson SP. Viscoelastic behavior of discrete human collagen fibrils. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2010 Jan 1;3(1):112-5. 5) Ryan ED, Herda TJ, Costa PB, Walter AA, Hoge KM, Stout JR, Cramer JT. Viscoelastic creep in the human skeletal muscle–tendon unit. European journal of applied physiology. 2010 Jan 1;108(1):207-11. 6) Kubo K, Ikebukuro T, Maki A, Yata H, Tsunoda N. Time course of changes in the human Achilles tendon properties and metabolism during training and detraining in vivo. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:2679–91. 7) Kubo K, Ikebukuro T, Yata H, Tsunoda N, Kanehisa H. Time course of changes in muscle and tendon properties during strength training and detraining. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:322–31. 8) de Boer MD, Maganaris CN, Seynnes OR, Rennie MJ, Narici MV. Time course of muscular, neural and tendinous adaptations to 23 day unilateral lower-limb suspension in young men. J Physiol. 2007;583:1079–91 History of Knee Pain It's about this time of year, every year, that people living in north of California think about strapping on skis for the winter. The most common concern is regarding knee integrity and readiness to ski. I like to group the concern into three groups:

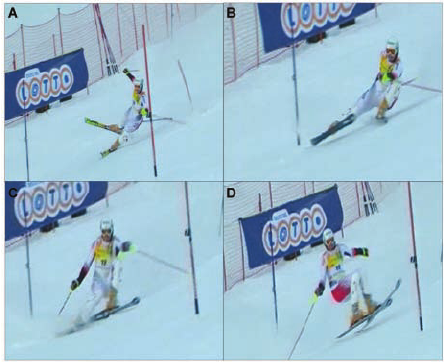

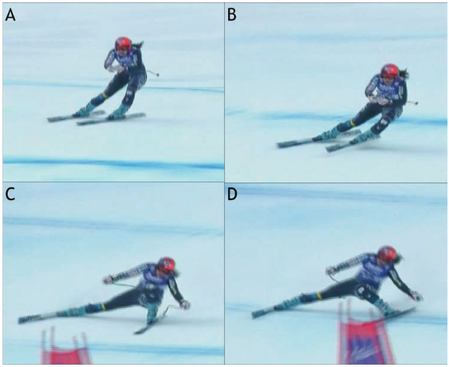

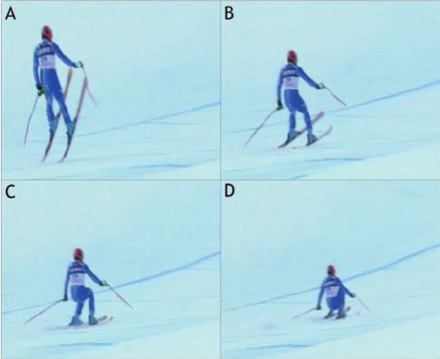

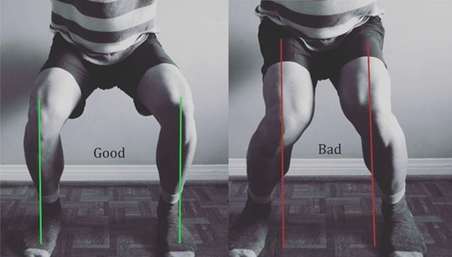

Chances are that if you fall into group 3, you will likely ski and have an injury-free season (but unfortunately there is always a first time for everything…). If you fall into group 1 or 2, you’ll likely appreciate the remainder of the article. Knowledge is power – use the following information to shape your training and awareness! Mechanism of Ski Injuries Fact The knee has two joints – the tibiofemoral joint and the patellofemoral joint. Skiing loads both joints tremendously, in different ways. The two most common knee injuries from skiing include ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) tears, and patellofemoral dysfunction (knee cap pain). ACL Tears ACL tears are acute, and often a result of catching an edge, crashes or poor landings. They often fall into one of three categories: 1) Slip Catch: Commonly seen while turning when the inside edge of the outer ski catches the snow surface, forcing the knee into a valgus collapse and internal rotation position (2). 2) Dynamic Snow Plow: When one of the ski edges accidentally engages the inside edge of the skis, and forces the lower leg to jerk inwards (valgus collapse). The tibia rapidly moves across the middle of the body and cause the valgus collapse of the knee. (1). 3) Landing Back-Weighted: A tactical error in jumping / landing and technique that leads to landing on the tails of the ski, which will stress the knee joint in an anterior/posterior shearing nature (1). Patellofemoral Pain Patellofemoral pain often comes on from an accumulation of poor or excessive loading. The most common fault (and easiest to identify) is a valgus collapse of the knee. You can also identify this by watching someone squat or lunge, or squat / jump, as seen below. If the knee has a tendency to collapse inwards, the hip is usually doing a poor job stabilizing the knee. Other possible reasons for patellofemoral pain include overuse of the quads (anterior chain dominance, too much skiing too soon), tight quads (causing compression of the patella) or weak quads (causing poor stabilization of the knee cap for the load being placed). Training for Healthy Knees and an Injury-Free Ski Season An entire training program for proper knee function is outside of the scope of this article, however a couple good examples include:

General loading principles to abide by include:

A reasonable list of exercises (from basic to advanced) include: Two Leg Focused Exercises Hopping (forward/backwards, side to side, diagonals) Squat Jumps Burpees (with jump) Box Jumps Lateral Box Jump Overs (side to side) Hurdle Bounds Single Leg Focused Exercises Ski Hops Jumping Lunge Single Leg Hopping (forward/backwards, side to side, diagonals) Single Leg Hopping (through cones or agility ladder) Single Leg Hurdle Bounds Perfecting Your Technique During the early part of the ski season, spend the first few ski days working on your technique. Perhaps some pointers from your friends or a ski instructor would be helpful? As you scroll up and review the possible injury mechanisms, remember that strength and, more importantly, technique are to blame for most ski injuries. Pre-Season Stoke Now is the time to make a game plan. If you are excited for ski season, let this fuel your training! Any level of commitment to pre-season strengthening is better than nothing! The ideal goal would be to get into the gym 3 times a week for strength training, but start with whatever you can commit to. If you currently have pain, and aren't sure where to start, make an appointment with a physiotherapist or sports medicine physician. See you out there! References 1) Bere, T., Flørenes, T. W., Krosshaug, T., Nordsletten, L., & Bahr, R. (2011). Events leading to anterior cruciate ligament injury in World Cup Alpine Skiing: a systematic video analysis of 20 cases. Br J Sports Med, bjsports-2011.

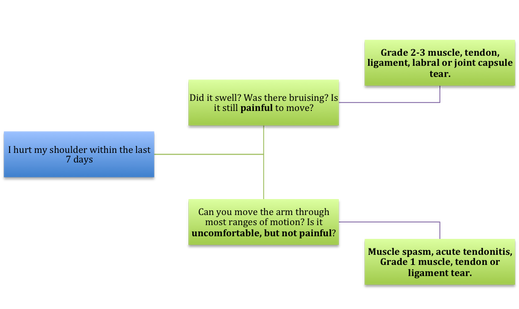

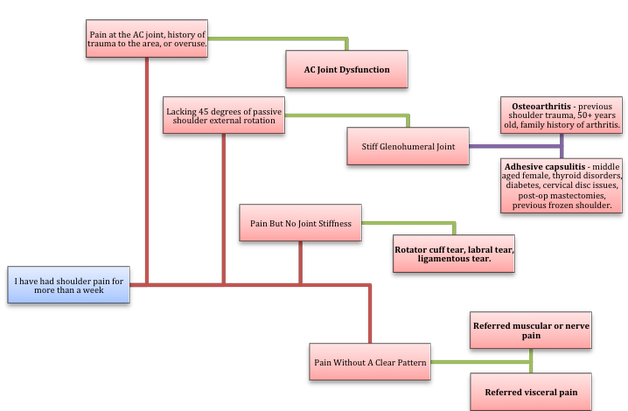

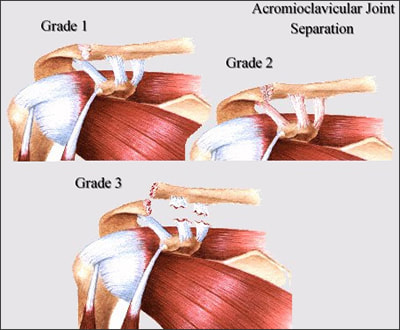

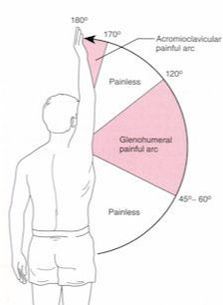

2) Bere, T., Mok, K. M., Koga, H., Krosshaug, T., Nordsletten, L., & Bahr, R. (2013). Kinematics of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in World Cup alpine skiing: 2 case reports of the slip-catch mechanism. The American journal of sports medicine, 41(5), 1067-1073. If Only Our Bodies Came With User Manuals! It's tough to know when its okay to push through pain or stiffness, or to know if the recent shoulder tweak that happened last week is of any importance. Over the last number of years I've picked up a number of strategies from research and experts in the sports medicine and orthopaedic world - I hope this can serve as a general guide! (NB - this is a blue print for simple shoulder injuries, and will not fit every situation. Use the following information as the guide that it is, and seek additional advice if you need further guidance!) Did You Hurt Your Shoulder Within The Last 7 Days? To start it off, if you've hurt your shoulder in the last 7 days, read through the following flow chart, and then the corresponding text below: Grade 2-3 muscle, tendon, ligament, labral or joint capsule tear If you experience significant pain, possibly with swelling or bruising, it is likely that you have significantly injured your soft tissues. While outliers exist (bone fracture or nerve involvement), it is most likely an issue related to a tear of a muscle, tendon, ligament, or the joint structure, If the pain in significant, a trip to the ER or family doctor may be the best first option. In terms of rehabilitation, it is probably best to let the shoulder heal for at least 7 days from the initial injury date before starting active rehab exercises. During this time you should see your local physiotherapist or sports medicine physician for an accurate diagnosis and to develop a treatment plan. During the first 7 days, you can support the shoulder with tape or a sling, apply ice (if you need to numb the pain), and perform pain-free range of motion. You should continue to exercise your lower body during this time. You can reasonably expect that there will be a range of motion limitation and/or strength reduction for at least 3 weeks from the date of the injury. It would be advisable to avoid loading the injured tissues with exercise for at least 3 weeks as the injury heals. As per standard tissue healing timelines, the injured tissues will not reach their full strength for up to 9-12 months in a healthy adult… so it is important that you do not re-injure it in the first 3-6 months (to be conservative). Muscle spasm, acute tendonitis, grade 1 muscle, tendon or ligament tear. If you've come to the conclusion that it's likely a muscle spasm, or minor muscle strain / ligament sprain, start immediately with soft tissue release, foam rolling, and gentle stretching into the areas of tightness. Within the first 3-7 days, start to do some light and pain-free resistance exercises to the surrounding muscles (e.g. easy rotator cuff exercises with a theraband). By the end of week 2 you should have loosened up most of the muscle tightness around the shoulder, and should be starting to gradually increase load/exercise for the shoulder. If your discomfort and limited range of motion is not gone within the first 2 weeks, get it assessed and treated. These small nagging injuries have a way of accumulating over the years and may predispose you to a more severe problem in the future. Have You Had Shoulder Pain For More Than 7 Days? This becomes more complicated as we have to discern between a number of different potential concerns. Acromioclavicular (AC) joint dysfunction - There are a few differed reasons that you may develop AC joint dysfunction. First, and most simple, is a direct hit to your shoulder. You will remember this happening, so in this case, its not too complicated. You will likely experience pain and joint laxity when you press on the AC joint, and in severe cases you may experience a 'separated shoulder' that looks like this: The good news about separated shoulders is that physiotherapy (as opposed to surgery) is often enough to help athletes and recreationalists return to their sports and daily activities pain free. If you do not remember a direct trauma, the following may apply to you: The AC joint is often the site of arthritis and come on from overuse or impact (most often seen in athletes (hockey, football, baseball, weight lifters, or overhead work). Pain and dysfunction from the AC joint often can cause impingement of the rotator cuff, and as such may present with muscle weakness, pain down the arm as far as the elbow, and a painful arc of motion. The symptoms that you experience during the arc of motion can help differentiate if it is just the joint that is irritable, or if there may be a rotator cuff impingement; If you have pain between 45-120 degrees abduction, but no pain before or after this range, then it is likely that you have an impingement of supraspinatus muscle (with or without an inflamed bursa). If you only have pain at the very top of this range of motion, it is likely that your AC joint is irritable. Assessment-informed treatment is often the key if it is a chronic pain: 1) You may benefit from other tests that can be done by a physiotherapist to assess joint integrity. 2) An X-ray may be of benefit to ensure there is no bone spur or congenital abnormality of the acromion, 3) A diagnostic ultrasound may be helpful to discern whether the supraspinatus tendon or subacromial bursa are irritated. Conservative treatment is the first-line treatment, as you will almost certainly have tightness and weakness of the surrounding shoulder musculature which may be causing secondary pain. A good assessment is usually needed to assess and treat the neck, thoracic spine, scapulothoracic rhythm, sternoclavicular joint mobility, scapulohumeral rhythm, and the AC joint. Most importantly, returning to a quality, pain-free exercise program will quicken the recovery. Differentiating Reasons for a Stiff Shoulder JointOne of the easiest ways to assess a stiff joint, is to look at passive range of motion, and try to assess the end-feel of the motion. If you are lacking 45 degrees of passive shoulder external rotation, and it feels like there is a capsular or joint restriction (hard end-feel), you likely fit into this category. Often, these cases require a medical approach to rule out other pathologies - be prepared to seek a referral to your family doctor or sports medicine physician for some imaging (to rule out sinister pathology or rule in arthritis), or blood work.  To assess passive shoulder external rotation, lay down on your back, and with you painful arm completely relaxed, use a broomstick or cane to gentle push the painful arm outwards (rotating the shoulder out). Keep your elbow relaxed and next to your ribcage. Remember... you are trying to assess the stiffness of the joint, so all muscles in the painful arm must remain relaxed! Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis If you have had a previous shoulder trauma, are 50+ years old or have a family history of arthritis, the most likely problem is that of glenohumeral osteoarthritis (could be from previous instability, or because of normal wear and tear associated with age). Manual therapy that focuses on improving joint capsule mobility is often required to make progress. Various joint injections exist that may help with lubrication of the joint, or inflammation within the joint. At home, patients can start with rolling tight muscles on the back of the shoulder joint to loosen any tissues that may be restricting the joint mobility. Ultimately, most progress will be made with the help of physiotherapy or medical intervention. Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder) The most likely alternative reason for a stiff shoulder is adhesive capsulitis. The strongest risk factor for developing adhesive capsulitis is being a peri-menopausal female. Other risk factors include thyroid disorders, diabetes, cervical disc issues, post-op mastectomies, a recent fall/trauma, and having a previous frozen shoulder. The shoulder seems to stiffen and become painful without a usual cause, and keeps patients awake at night. We see patterns of limited external rotation, internal rotation and flexion. If the diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis is reached, patients may find a cortisone injection helpful in the early stages. There has also been some clinical evidence showing that manipulation of the fibrotic joint under a nerve block may be of benefit.. Otherwise, regular physiotherapy that includes stretching, shockwave therapy, and manual therapy (soft tissue release, IMS, and joint mobilizations) will provide the greatest benefit. Shoulder Pain with Limited Active Range of Motion but Without Joint Stiffness If you do not have a stiff glenohumeral joint (more than 45 degrees passive external rotation), yet there is shoulder pain and limited active range of motion, a skilled practitioner will take you through a number of tests to help determine whether the pain is coming from a rotator cuff tear, labral tear or ligamentous tear (this is usually preceded by a dislocation / subluxation). The diagnosis of a tear must be ascertained by the clinic history, movement exam, special tests, response to treatment, and possibly ultrasound/MRI/other imaging. For the purposes of this article I am going to avoid the discussion of which special tests may be useful for diagnosing tears; This is a contentious issue as most special tests are... not that special; they are not very specific toward testing just one tissue and often lead to false positives. This topic is beyond the scope of this article. Shoulder Pain Without a Clear Pattern Very few patients fit into this category, so if you think that you do, its likely that you've missed something during your self-assessment. Excluding this caveat, I write this last section for completion. 1. Referred Pain - A painful shoulder that has no pattern of painful movement may be experiencing referred symptoms from the neck, diaphragm or the heart. 2. Cancer/Metastases - A number of different viscera can create pain into the shoulder region. Most likely include the lung, liver, and gallbladder. Typically you will experience unrelenting pain (nothing can make the symptoms change), difficulty sleeping at night, excessive fatigue, weight loss, a fever, or any number of other changes in your normal health. See the following link for more information: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-basics/signs-and-symptoms-of-cancer.html 3. Pain Syndromes - Widespread hypersensitivity/hyperalgesia may also affect the shoulder. Various non-specific pain syndromes may create shoulder pain and include: Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome, Myofascial Pain Syndrome & Fibromyalgia. A Final Note In most cases of shoulder pain, an exercise program is the key component necessary to return to full function without pain. In cases of partial thicken tendon tears, full thickness tendon tears or subacromial impingement, a specific and progressive exercise program often provides improved function, reduced pain and reduced need of surgery when compared with a general exercise program (1, 2, 3). My typical progression in the clinic is: 1) Determine if patient has any red flags that indicate immediate medical assessment / intervention. 2) Assess full body movement to determine how one area of the body may be affecting another. 3) Assess the shoulder for joint integrity, ligament and tendon damage, flexibility and strength. 4) Perform manual therapy, IMS and shockwave (if needed) to reduce pain and improve joint position/posture. 5) Provide patient with a specific, graduated exercise program. 6) Assess progress of the shoulder and repeat 2-6 as indicated until full function is .recovered, or a referral is indicated to see a sports medicine specialist. References (1) Björnsson Hallgren, H. C., Adolfsson, L. E., Johansson, K., Öberg, B., Peterson, A., & Holmgren, T. M. (2017). Specific exercises for subacromial pain: Good results maintained for 5 years. Acta Orthopaedica, 1-6.

(2) Holmgren, T., Hallgren, H. B., Öberg, B., Adolfsson, L., & Johansson, K. (2012). Effect of specific exercise strategy on need for surgery in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: randomised controlled study. Bmj, 344, e787. (3) Kukkonen, J., Joukainen, A., Lehtinen, J., Mattila, K. T., Tuominen, E. K. J., Kauko, T., & Äärimaa, V. (2014). Treatment of non-traumatic rotator cuff tears. Bone Joint J, 96(1), 75-81. |

Have you found these article to be informative, helpful, or enjoyable to read? If so, please visit my Facebook page by clicking HERE, or click the Like button below to be alerted of all new articles!

Author

Jacob Carter lives and works in Canmore, Alberta. He combines research evidence with clinical expertise to educate other healthcare professionals, athletes, and the general public on a variety of health topics. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed