|

Recovering from an injury can be a nuanced process - there are some symptoms that you should listen to and others that aren’t so important, poor information abounds during searches on Dr. Google, there are friendly recommendations to try certain products, drugs or stretches, and just when you think it is okay to resume your normal activities pain may re-surge. It can be confusing… That being said, if you focus your attention on the overarching principles of an effective rehab, recovery doesn’t have to be complicated! Here are few key areas that anyone can assess and will help to simply your return to wellness: 1. Time A) If you’ve sustained an injury, rehab will take time. Determining its severity can help you plan your rehab timeline. If it’s a small injury (micro-tearing or grade 1 sprain/strain), allow three days of relative rest for the injured area and slowly start to return to your sport. If it was a moderate or severe injury (grade 2-3 sprain / strain, fracture), you will need more time to allow the injury’s wound margins to heal back together. Due to the magnitude of a more severe injury you will likely benefit from a support (see below) and clever ways of modifying activity/programming. B) If you are not seeing many signs of improvement from your injury within a week, consulting a health care provider (Physio/Doctor) is a good idea. Diagnosing the injury and its severity will be important for your rehab strategy and long-term success. 2. Exercise A) Make sure that you perform exercises specific for your injury/dysfunction. Your exercises should address all three of the following:

3. Supports A) Your recovery from an injury may be uncomfortable but it needn’t be exquisitely painful. Utilizing walking aids (crutches/cane/walking poles), braces, taping techniques, medication (oral, topical or injections) or certain types of shoes/orthotics may help to alleviate some of your pain. These supports are not be relied on for very long, but can help reduce the harmful effects of feeling too much pain during your recovery. 4. Activity level A). Many of my clients see me because they have slow progress or are seeing no progress. This is often because #2 is not being addressed and clients are often doing too much or too little activity in their day to day life. Determining the appropriate amount of activity requires:

Concluding Remarks Creating a good rehab program is an art. Of course there are other items to consider whilst recovering from an injury, but if you can dial in these four key areas it should help with setting realistic expectations and executing a planned recovery.

As always, if you have any questions feel free to send me an email or leave a comment!

2 Comments

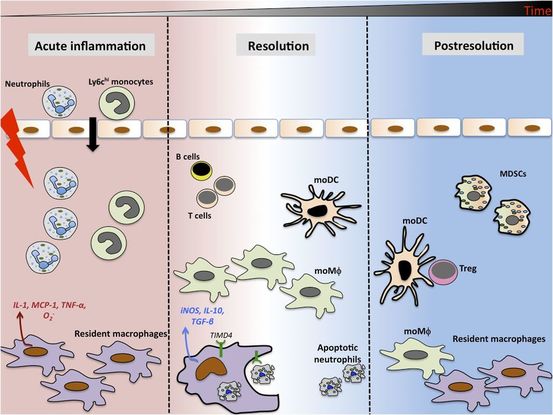

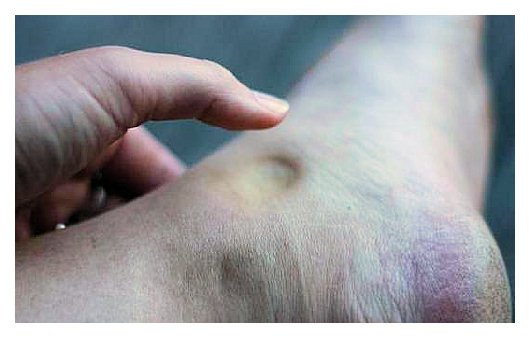

As written for www.one-wellness.ca We try to improve the body’s natural response to injury in many different ways. Health professionals around the world offer products and techniques that promise the greatest reduction in inflammation and swelling, believing that their product can rise above the competition… But why? Is it helpful to alter these responses, and is it even possible that we can alter these responses? For the most pragmatic answers, we can rely only on research… Definitions Understanding the differences in medical terminology allows us to better understand what processes are happening in our body. With this higher level of understanding, both practitioners and patients can better communicate what is happening in the body to achieve optimal outcomes. Swelling and inflammation of are often thought of as synonymous terms, however they have distinct definitions and applications. Inflammation: Inflammation is “a local response to cellular injury that is marked by capillary dilatation, leukocytic infiltration, redness, heat, and pain and that serves as a mechanism initiating the elimination of noxious agents and of damaged tissue” (1). Swelling: From Greek, the word ‘oídēma’ translates to ‘swelling’ (2). ‘Edema’ suggests “an abnormal infiltration and excess accumulation of serous fluid in connective tissue or in a serous cavity” (3). To briefly summarize, inflammation is a cellular response to tissue injury and may result in swelling, however swelling can actually occur within the body without the process of inflammation. A few common examples of swelling occurring within the body, in the absence of inflammation include: Lymphedema (failure of lymphatic drainage system to circulate blood plasma, and immune system regulators), cerebral edema (accumulation of extracellular fluid in the brain), pulmonary edema (accumulation of extracellular fluid in the lung). A few common examples of swelling that occurs within the body with inflammation as the causation includes: Acute tissue injury (fractures, sprains, strains), dermatitis (inflammation of the dermis layer of the skin), thrombophlebitis (inflammation of vein due to a blood clot). Treating Inflammation Is it possible to alter the inflammatory response? Is it helpful to alter the inflammatory response? Over the last few decades there has been a culture of reducing inflammation immediately following acute injuries. However recent research has been changing the way clinicians should treat acute injuries: Anti-inflammatory medication can decrease the inflammatory response, but they may impair healing: In addition to their potential side effects (affecting GI tract, kidneys and cardiovascular systems), using NSAIDs (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) may result in: a) Impaired bone healing after a fracture (4-9). b) Impaired tendon healing after an acute injury (10-11). c) No improvements in chronic tendinopathies, as there is no active inflammatory process (12). d) No improvement or possible small improvements in functional recovery In acute ligament injuries (13-18). Although one study found that using NSAIDs resulted in decreased pain and improved functional status, they also found a greater risk of adverse affects compared to using only analgesics. Also, one review of the literature found that acetaminophen is as effective as NSAIDs for pain reduction after musculoskeletal injury (19). These new results teach a few lessons: 1) The inflammatory mediators (e.g. prostaglandins, and cytokines) in inflammation help to initiate the subsequent stages of healing. 2) Removal of inflammation from an acute injury may harm the subsequent stages of healing. 3) In many cases, acetaminophen (e.g. Tylenol) will help to reduce pain as much as the use of anti-inflammatory medications, and will not impair healing. The overall justification for the use of the RICE principle (Rest, Ice, Compression Elevation) is very practical and helps minimize bleeding into the injury site. However, there has not been a single randomized, clinical trial to validate the effectiveness of the entire principle. 50 There is some support for each item, including immediate rest, and elevation to help in managing the accumulation of interstitial fluid (20). Summary: As much as possible restrict the usage of NSAIDs, employ the RICE principle, and if pain requires additional control then consider the use of other analgesic medications (e.g. acetaminophen, opiods, etc). It is a counterproductive goal to attempt to resolve all inflammation around the acute injury site. Treating Swelling Is it possible to alter swelling caused by acute injuries? Is it helpful to alter the swelling? It is possible to alter swelling that has been caused by acute injuries. In the following photos you can see that with appropriate rehabilitation, swelling improves. Unlike inflammation, it is in your best interest to reduce the amount of swelling at the local injury site. Depending on the amount of swelling, it can result in nerve compression, and restricted joint mobility making it painful and difficult to move the affected area (21). There is no benefit of allowing this swelling to stagnate as it will increase the level of irritability of the injury site and cause further deconditioning. While there are numerous modalities that purport to increase blood flow (e.g. interferential current, acupuncture, laser, ultrasound, etc., they majority lack substantial research and are unnecessary to resolve 99% of cases. In addition to the RICE principle mentioned previously, there are two supported methods to reduce swelling at the injury site: Movement - Regular movement of the affected joint, or at least the joints above and below should help pump the excess fluid back toward your heart using the lymphatic system. In addition, when able, start to perform cycling, swimming, rowing or perform upper body exercises. Massage - Stroking the affected area toward your heart using firm pressure may help move the excess fluid out of that area. There are many physiotherapists and massage therapists that have extra training in lymphatic drainage techniques that may be able to guide you, if you have been experiencing poor outcomes. References 1. Merriam-Webster Dictionary [Internet]. 2018. Inflammation; 2018-07-28. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inflammation

2. Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus 3. Merriam-Webster Dictionary [Internet]. 2018. Edema; 2018-07-28. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/edema 4. Matsumoto MA, De Oliveira A, Ribeiro Junior PD, et al. Short-term administration of non-selective and selective COX-2 NSAIDs do not interfere with bone repair in rats. J Mol Histol. 2008;39:381-387. 5. Endo K, Sairyo K, Komatsubara S, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor delays fracture healing in rats. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:470-474. 6. O’Connor JP, Capo JT, Tan V, et al. A comparison of the effects of ibuprofen and rofecoxib on rabbit fibula osteotomy healing. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:597-605. 7. Bergenstock M, Min W, Simon AM, et al. A comparison between the effects of acetaminophen and celecoxib on bone fracture healing in rats. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:717-723. 8. Giannoudis PV, MacDonald DA, Matthews SJ, et al. Nonunion of femoral diaphysis: the influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B:655-658. 9. Bhattacharyya T, Levin R, Vrahas MS, Solomon DH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and nonunion of humeral shaft fracture. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:364-367. 10. Elder CL, Dahners LE, Weinhold PS. A cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor impairs ligament healing in the rat. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:801-805. 11. Ferry ST, Dahners LE, Afshari HM, Weinhold PS. The effects of common anti-inflammatory drugs on the healing rat patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1326-1333. 12. Aström M, Westlin N. No effect of piroxicam on achilles tendinopathy: a randomized study of 70 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:631-634. 13. Lane LB, Boretz RS, Stuchin SA. Treatment of de Quervain’s disease: role of conservative management. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26:258-260. 14. Dahners LE, Gilbert JA, Lester GE, et al. The effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug on the healing of ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:641-646. 15. Moorman CT 3rd, Kukreti U, Fenton DC, Belkoff SM. The early effect of ibuprofen on the mechanical properties of healing medial collateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:738-741. 16. Ekman EF, Fiechtner JJ, Levy S, Fort JG. Efficacy of celecoxib versus ibuprofen in the treatment of acute pain: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial in acute ankle sprain. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2002;31:445-451. 17. Ekman EF, Ruoff G, Kuehl K, et al. The COX-2 specific inhibitor Valdecoxib versus tramadol in acute ankle sprain: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:945-955. 18. Slatyer MA, Hensley MJ, Lopert R. A randomized controlled trial of piroxicam in the management of acute ankle sprain in Australian Regular Army recruits. The kapooka ankle sprain study. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:544-553. 19. Feucht CL, Patel DR. Analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications in sports: use and abuse. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:751-774. 20. van den Bekerom MP, Struijs PA, Blankevoort L, Welling L, Van Dijk CN, Kerkhoffs GM. What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults?. J Athlet Train. 2012 Jul;47(4):435-43. 21. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s Principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. 18th ed; 2011. While manual therapy and education may play a crucial role in injury rehabilitation, injuries and pain respond the best in the long-term to progressive loading through exercise. In fact, exercise is said to be "the closest thing to a miracle cure" (1), and is widely accepted as the means through which you can attain complete recovery. Prescribing exercise can be intimidating for some therapists, so I wanted to provide some facts and guidelines that may help make this easier! Fitting the Diagnosis to the Injury Attaining an accurate diagnosis CAN be difficult, but is often the first stage to developing a treatment plan, including exercise. 1. Do we know the actual pathology/diagnosis? An over-reliance on imaging and unreliable ‘special’ tests may mean that the true pathology (AKA reason for the client’s pain) may not fully be understood. A) Imaging typically looks at the injury site at a specific moment in time. To develop a true understanding of the pathology, this information must be examined along with the patient's subjective history and movement patterns. A common example in knee pain would be that an x-ray finding of moderate osteoarthritis of the patella is an additional finding, when the true reason for the patient's knee pain is trigger points in the quadriceps caused by suboptimal movement control. B) Many Special Tests are not that special. A special test should look to confirm suspicions of a specific diagnosis - they should not be used initially when developing a diagnosis. We know that many special tests lack sensitivity and specificity, and as a result are not helpful in confirming the diagnosis (even with a proper history and objective exam). Nicklaus Biederwolf, a physiotherapist and researcher, has this to say about special tests specific to the shoulder: "A great lack of consistency with regard to how, when, and what special tests to use in clinical examination for shoulder differential diagnosis is evident" (2). C) Different health care practitioners may develop different diagnoses that fit the information gathered during their assessment, and their bias. It is important to do a comprehensive assessment (including the client's previous medical history, mechanism of injury, pattern of pain, global movement patterns, and a specific joint/tissue/nervous system/vascular assessment). 2. Without imaging, we depend on clinical patterns to develop an accurate diagnosis, however similar pathologies may behave differently in the clinical setting. For example a partial thickness supraspinatus tear (one of the shoulder's rotator cuff muscles) may behave differently in one client versus other clients - and this may be for a wide variety of reasons: A) Anatomical variations: The acromion (a protrusion on our shoulder blade, under which the supraspinatus tendon glides) come in all shapes and sizes. The same applies to the rest of our bones, and muscles/tendons in our body - we are not as symmetrical and standardized as you may think! B) Regional Interdependence: Canadian Physiotherapists are known as 'The Movement Specialists' (3), so keep connecting the dots to determine how one area of the body may be affecting another! The thoracic spine, neck, scapula and all of its connecting muscles and ligaments alter the dynamic control and posture of the shoulder, which ultimately impact the supraspinatus tendon. C) Variations in nociception (sensing pain): Fewer pain nerve endings near the injury site, previous injury to nerve or blood supply at the area, or differences in central nervous system perception of pain on a global level will affect how a patient feels potentially harmful stimuli. D) Multiple injuries: A mechanism of injury that may tear the supraspinatus may also injure other tissues in the area. For example, there could also be an injury of the labrum, chondral surface of the humerus, biceps tendon, pec major, or subacromial bursa. It is nearly impossible to identify/distinguish all of these pathologies in the clinic without imaging... BUT does it really matter? Read on! What To Do.. in a World of Unknowns? It can all get quite confusing.. The items above paint a muddled picture: It can be quite difficult to come up with the correct diagnosis due to many(!!!) factors. Luckily, despite this fact, there are a few things we can do that will promote successful recovery. 1. It may be more important to focus on movement deficits first. Our bodies are exceptional at healing themselves. In fact, the best athletes in the world are the ones that recover the quickest (from training, games, or injuries). Most of the time, the injured tissue will heal on their own, but will leave us with tight muscles and poor movement patterns as a result of compensation. This means that pursuing imaging and specialist appointments may just end up being a waste of time, health care dollars, and stress. To start, the patient shoulder obtain a couple of opinions (physician and physiotherapist) to determine whether medical testing may be needed. Following these opinions, it is usually best to focus on improving flexibility and movement control. 2. Zoom out; Broaden your perspective! Often we warn patients against performing certain exercises, based on the fact that they have a certain pathology (e.g. with an acute partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon, stay away from dips or deep bench press). Take a step back and look at global movement patterns - are there any other restrictions / dysfunctions that you could work on first? In our case example: Do you need to work on thoracic mobility, activating scapular upward rotators, releasing scapular downward rotators, activating deep neck flexors, releasing posterior rotator cuff, releasing adhesions at the interface of pec major / supraspinatus / long head of biceps? Maybe a further step back would even suggest asymmetries in lower body, lower back, or neck strength/mobility. 3. Prescribing the exercise. Suggesting that the patient does a specific exercise is not enough. Ensure that the correct exercise is performed correctly; Spend time on coaching form and don’t expect that your client knows how to do the exercise properly. Lastly, discuss the importance of correct exercise: 1. Volume 2. Intensity 3. Rest 4. Tempo By changing these four variables, we can ultimately train the tissue work for its intended purpose and improve A) Muscular endurance B) Muscular power C) Muscular reactivity (plyometrics) D) Tendon loading capacity 4. Test, and Re-Test If you've taught the exercises well, allow adequate time for a beneficial result to occur, and re-test the client's functional deficits. 5. Lastly, a client’s most effective exercises may change overtime due to movement quality, tissue quality, perceived effort/challenge, ability to recover quickly, or the applicability to sport and life specific challenges. Follow up a few weeks or months down the road to provide the best possible care to your client. References (1) Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Exercise: The miracle cure and the role of the doctor in promoting it. AOMRC.org.uk. 2015 Feb

(2) Biederwolf, Nicklaus E. "A proposed evidence-based shoulder special testing examination algorithm: clinical utility based on a systematic review of the literature." International journal of sports physical therapy 8.4 (2013): 427. 3) Physiotherapy Alberta: About Physiotherapy. Accessed February 1, 2018. https://www.physiotherapyalberta.ca/public_and_patients/about_physiotherapy |

Have you found these article to be informative, helpful, or enjoyable to read? If so, please visit my Facebook page by clicking HERE, or click the Like button below to be alerted of all new articles!

Author

Jacob Carter lives and works in Canmore, Alberta. He combines research evidence with clinical expertise to educate other healthcare professionals, athletes, and the general public on a variety of health topics. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed