|

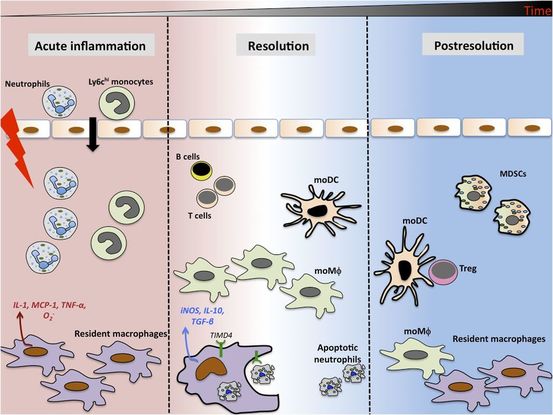

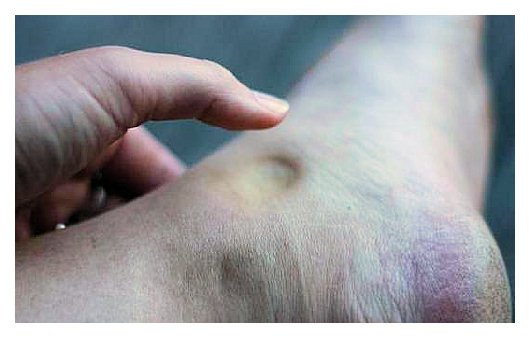

As written for www.one-wellness.ca We try to improve the body’s natural response to injury in many different ways. Health professionals around the world offer products and techniques that promise the greatest reduction in inflammation and swelling, believing that their product can rise above the competition… But why? Is it helpful to alter these responses, and is it even possible that we can alter these responses? For the most pragmatic answers, we can rely only on research… Definitions Understanding the differences in medical terminology allows us to better understand what processes are happening in our body. With this higher level of understanding, both practitioners and patients can better communicate what is happening in the body to achieve optimal outcomes. Swelling and inflammation of are often thought of as synonymous terms, however they have distinct definitions and applications. Inflammation: Inflammation is “a local response to cellular injury that is marked by capillary dilatation, leukocytic infiltration, redness, heat, and pain and that serves as a mechanism initiating the elimination of noxious agents and of damaged tissue” (1). Swelling: From Greek, the word ‘oídēma’ translates to ‘swelling’ (2). ‘Edema’ suggests “an abnormal infiltration and excess accumulation of serous fluid in connective tissue or in a serous cavity” (3). To briefly summarize, inflammation is a cellular response to tissue injury and may result in swelling, however swelling can actually occur within the body without the process of inflammation. A few common examples of swelling occurring within the body, in the absence of inflammation include: Lymphedema (failure of lymphatic drainage system to circulate blood plasma, and immune system regulators), cerebral edema (accumulation of extracellular fluid in the brain), pulmonary edema (accumulation of extracellular fluid in the lung). A few common examples of swelling that occurs within the body with inflammation as the causation includes: Acute tissue injury (fractures, sprains, strains), dermatitis (inflammation of the dermis layer of the skin), thrombophlebitis (inflammation of vein due to a blood clot). Treating Inflammation Is it possible to alter the inflammatory response? Is it helpful to alter the inflammatory response? Over the last few decades there has been a culture of reducing inflammation immediately following acute injuries. However recent research has been changing the way clinicians should treat acute injuries: Anti-inflammatory medication can decrease the inflammatory response, but they may impair healing: In addition to their potential side effects (affecting GI tract, kidneys and cardiovascular systems), using NSAIDs (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) may result in: a) Impaired bone healing after a fracture (4-9). b) Impaired tendon healing after an acute injury (10-11). c) No improvements in chronic tendinopathies, as there is no active inflammatory process (12). d) No improvement or possible small improvements in functional recovery In acute ligament injuries (13-18). Although one study found that using NSAIDs resulted in decreased pain and improved functional status, they also found a greater risk of adverse affects compared to using only analgesics. Also, one review of the literature found that acetaminophen is as effective as NSAIDs for pain reduction after musculoskeletal injury (19). These new results teach a few lessons: 1) The inflammatory mediators (e.g. prostaglandins, and cytokines) in inflammation help to initiate the subsequent stages of healing. 2) Removal of inflammation from an acute injury may harm the subsequent stages of healing. 3) In many cases, acetaminophen (e.g. Tylenol) will help to reduce pain as much as the use of anti-inflammatory medications, and will not impair healing. The overall justification for the use of the RICE principle (Rest, Ice, Compression Elevation) is very practical and helps minimize bleeding into the injury site. However, there has not been a single randomized, clinical trial to validate the effectiveness of the entire principle. 50 There is some support for each item, including immediate rest, and elevation to help in managing the accumulation of interstitial fluid (20). Summary: As much as possible restrict the usage of NSAIDs, employ the RICE principle, and if pain requires additional control then consider the use of other analgesic medications (e.g. acetaminophen, opiods, etc). It is a counterproductive goal to attempt to resolve all inflammation around the acute injury site. Treating Swelling Is it possible to alter swelling caused by acute injuries? Is it helpful to alter the swelling? It is possible to alter swelling that has been caused by acute injuries. In the following photos you can see that with appropriate rehabilitation, swelling improves. Unlike inflammation, it is in your best interest to reduce the amount of swelling at the local injury site. Depending on the amount of swelling, it can result in nerve compression, and restricted joint mobility making it painful and difficult to move the affected area (21). There is no benefit of allowing this swelling to stagnate as it will increase the level of irritability of the injury site and cause further deconditioning. While there are numerous modalities that purport to increase blood flow (e.g. interferential current, acupuncture, laser, ultrasound, etc., they majority lack substantial research and are unnecessary to resolve 99% of cases. In addition to the RICE principle mentioned previously, there are two supported methods to reduce swelling at the injury site: Movement - Regular movement of the affected joint, or at least the joints above and below should help pump the excess fluid back toward your heart using the lymphatic system. In addition, when able, start to perform cycling, swimming, rowing or perform upper body exercises. Massage - Stroking the affected area toward your heart using firm pressure may help move the excess fluid out of that area. There are many physiotherapists and massage therapists that have extra training in lymphatic drainage techniques that may be able to guide you, if you have been experiencing poor outcomes. References 1. Merriam-Webster Dictionary [Internet]. 2018. Inflammation; 2018-07-28. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inflammation

2. Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus 3. Merriam-Webster Dictionary [Internet]. 2018. Edema; 2018-07-28. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/edema 4. Matsumoto MA, De Oliveira A, Ribeiro Junior PD, et al. Short-term administration of non-selective and selective COX-2 NSAIDs do not interfere with bone repair in rats. J Mol Histol. 2008;39:381-387. 5. Endo K, Sairyo K, Komatsubara S, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor delays fracture healing in rats. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:470-474. 6. O’Connor JP, Capo JT, Tan V, et al. A comparison of the effects of ibuprofen and rofecoxib on rabbit fibula osteotomy healing. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:597-605. 7. Bergenstock M, Min W, Simon AM, et al. A comparison between the effects of acetaminophen and celecoxib on bone fracture healing in rats. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:717-723. 8. Giannoudis PV, MacDonald DA, Matthews SJ, et al. Nonunion of femoral diaphysis: the influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B:655-658. 9. Bhattacharyya T, Levin R, Vrahas MS, Solomon DH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and nonunion of humeral shaft fracture. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:364-367. 10. Elder CL, Dahners LE, Weinhold PS. A cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor impairs ligament healing in the rat. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:801-805. 11. Ferry ST, Dahners LE, Afshari HM, Weinhold PS. The effects of common anti-inflammatory drugs on the healing rat patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1326-1333. 12. Aström M, Westlin N. No effect of piroxicam on achilles tendinopathy: a randomized study of 70 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:631-634. 13. Lane LB, Boretz RS, Stuchin SA. Treatment of de Quervain’s disease: role of conservative management. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26:258-260. 14. Dahners LE, Gilbert JA, Lester GE, et al. The effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug on the healing of ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:641-646. 15. Moorman CT 3rd, Kukreti U, Fenton DC, Belkoff SM. The early effect of ibuprofen on the mechanical properties of healing medial collateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:738-741. 16. Ekman EF, Fiechtner JJ, Levy S, Fort JG. Efficacy of celecoxib versus ibuprofen in the treatment of acute pain: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial in acute ankle sprain. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2002;31:445-451. 17. Ekman EF, Ruoff G, Kuehl K, et al. The COX-2 specific inhibitor Valdecoxib versus tramadol in acute ankle sprain: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:945-955. 18. Slatyer MA, Hensley MJ, Lopert R. A randomized controlled trial of piroxicam in the management of acute ankle sprain in Australian Regular Army recruits. The kapooka ankle sprain study. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:544-553. 19. Feucht CL, Patel DR. Analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications in sports: use and abuse. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:751-774. 20. van den Bekerom MP, Struijs PA, Blankevoort L, Welling L, Van Dijk CN, Kerkhoffs GM. What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults?. J Athlet Train. 2012 Jul;47(4):435-43. 21. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s Principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. 18th ed; 2011.

2 Comments

|

Have you found these article to be informative, helpful, or enjoyable to read? If so, please visit my Facebook page by clicking HERE, or click the Like button below to be alerted of all new articles!

Author

Jacob Carter lives and works in Canmore, Alberta. He combines research evidence with clinical expertise to educate other healthcare professionals, athletes, and the general public on a variety of health topics. Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed